Copper

Did you know...

The articles in this Schools selection have been arranged by curriculum topic thanks to SOS Children volunteers. Sponsoring children helps children in the developing world to learn too.

| Copper | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

29Cu

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

red-orange metallic luster Native copper (~4 cm in size) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name, symbol, number | copper, Cu, 29 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pronunciation | / ˈ k ɒ p ər / KOP-ər | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metallic category | transition metal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, period, block | 11, 4, d | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight | 63.546(3) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

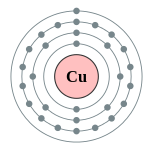

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s1 2, 8, 18, 1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Middle Easterns ( 9000 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.96 g·cm−3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Liquid density at m.p. | 8.02 g·cm−3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1357.77 K, 1084.62 °C, 1984.32 °F | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2835 K, 2562 °C, 4643 °F | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 13.26 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 300.4 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.440 J·mol−1·K−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vapor pressure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +1, +2, +3, +4 (mildly basic oxide) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 1.90 (Pauling scale) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies ( more) |

1st: 745.5 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 1957.9 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 3555 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | 128 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 132±4 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 140 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | (20 °C) 16.78 nΩ·m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 401 W·m−1·K−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | (25 °C) 16.5 µm·m−1·K−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound (thin rod) | ( r.t.) (annealed) 3810 m·s−1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 110–128 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 48 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 140 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 3.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 369 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 874 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7440-50-8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most stable isotopes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main article: Isotopes of copper | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from Latin: cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; a freshly exposed surface has a reddish-orange colour. It is used as a conductor of heat and electricity, a building material, and a constituent of various metal alloys.

The metal and its alloys have been used for thousands of years. In the Roman era, copper was principally mined on Cyprus, hence the origin of the name of the metal as сyprium (metal of Cyprus), later shortened to сuprum. Its compounds are commonly encountered as copper(II) salts, which often impart blue or green colors to minerals such as azurite and turquoise and have been widely used historically as pigments. Architectural structures built with copper corrode to give green verdigris (or patina). Decorative art prominently features copper, both by itself and as part of pigments.

Copper is essential to all living organisms as a trace dietary mineral because it is a key constituent of the respiratory enzyme complex cytochrome c oxidase. In molluscs and crustacea copper is a constituent of the blood pigment hemocyanin, which is replaced by the iron-complexed hemoglobin in fish and other vertebrates. The main areas where copper is found in vertebrate animals are liver, muscle and bone. In sufficient concentration, copper compounds are poisonous to higher organisms and are used as bacteriostatic substances, fungicides, and wood preservatives.

Characteristics

Physical

Copper, silver and gold are in group 11 of the periodic table, and they share certain attributes: they have one s-orbital electron on top of a filled d- electron shell and are characterized by high ductility and electrical conductivity. The filled d-shells in these elements do not contribute much to the interatomic interactions, which are dominated by the s-electrons through metallic bonds. Contrary to metals with incomplete d-shells, metallic bonds in copper are lacking a covalent character and are relatively weak. This explains the low hardness and high ductility of single crystals of copper. At the macroscopic scale, introduction of extended defects to the crystal lattice, such as grain boundaries, hinders flow of the material under applied stress thereby increasing its hardness. For this reason, copper is usually supplied in a fine-grained polycrystalline form, which has greater strength than monocrystalline forms.

The low hardness of copper partly explains its high electrical conductivity (59.6×106 S/m) and thus also high thermal conductivity, which are the second highest among pure metals at room temperature. This is because the resistivity to electron transport in metals at room temperature mostly originates from scattering of electrons on thermal vibrations of the lattice, which are relatively weak for a soft metal. The maximum permissible current density of copper in open air is approximately 3.1×106 A/m2 of cross-sectional area, above which it begins to heat excessively. As with other metals, if copper is placed against another metal, galvanic corrosion will occur.

Together with caesium and gold (both yellow), and osmium (bluish), copper is one of only four elemental metals with a natural colour other than gray or silver. Pure copper is orange-red and acquires a reddish tarnish when exposed to air. The characteristic color of copper results from the electronic transitions between the filled 3d and half-empty 4s atomic shells – the energy difference between these shells is such that it corresponds to orange light. The same mechanism accounts for the yellow colour of gold and caesium.

Chemical

Copper forms a rich variety of compounds with oxidation states +1 and +2, which are often called cuprous and cupric, respectively. It does not react with water, but it slowly reacts with atmospheric oxygen forming a layer of brown-black copper oxide. In contrast to the oxidation of iron by wet air, this oxide layer stops the further, bulk corrosion. A green layer of verdigris (copper carbonate) can often be seen on old copper constructions, such as the Statue of Liberty, the largest copper statue in the world built using repoussé and chasing. Copper tarnishes when exposed to hydrogen sulfides and other sulfides, which react with it to form various copper sulfides on the surface. Oxygen-containing ammonia solutions give water-soluble complexes with copper, as do oxygen and hydrochloric acid to form copper chlorides and acidified hydrogen peroxide to form copper(II) salts. Copper(II) chloride and copper comproportionate to form copper(I) chloride.

Isotopes

There are 29 isotopes of copper. 63Cu and 65Cu are stable, with 63Cu comprising approximately 69% of naturally occurring copper; they both have a spin of 3/2. The other isotopes are radioactive, with the most stable being 67Cu with a half-life of 61.83 hours. Seven metastable isotopes have been characterized, with 68mCu the longest-lived with a half-life of 3.8 minutes. Isotopes with a mass number above 64 decay by β-, whereas those with a mass number below 64 decay by β+. 64Cu, which has a half-life of 12.7 hours, decays both ways.

62Cu and 64Cu have significant applications. 64Cu is a radiocontrast agent for X-ray imaging, and complexed with a chelate can be used for treating cancer. 62Cu is used in 62Cu-PTSM that is a radioactive tracer for positron emission tomography.

Occurrence

Copper is synthesized in massive stars and is present in the Earth's crust at a concentration of about 50 parts per million (ppm), where it occurs as native copper or in minerals such as the copper sulfides chalcopyrite and chalcocite, copper carbonates azurite and malachite and the copper(I) oxide mineral cuprite. The largest mass of elemental copper discovered weighed 420 tonnes and was found in 1857 on the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan, US. Native copper is a polycrystal, with the largest described single crystal measuring 4.4×3.2×3.2 cm.

Production

Most copper is mined or extracted as copper sulfides from large open pit mines in porphyry copper deposits that contain 0.4 to 1.0% copper. Examples include Chuquicamata in Chile, Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah, United States and El Chino Mine in New Mexico, United States. According to the British Geological Survey, in 2005, Chile was the top mine producer of copper with at least one-third world share followed by the United States, Indonesia and Peru. Copper can also be recovered through the In-situ leach process. Several sites in the state of Arizona are considered prime candidates for this method. The amount of copper in use is increasing and the quantity available is barely sufficient to allow all countries to reach developed world levels of usage.

Reserves

Copper has been in use at least 10,000 years, but more than 95% of all copper ever mined and smelted has been extracted since 1900. As with many natural resources, the total amount of copper on Earth is vast (around 1014 tons just in the top kilometer of Earth's crust, or about 5 million years worth at the current rate of extraction). However, only a tiny fraction of these reserves is economically viable, given present-day prices and technologies. Various estimates of existing copper reserves available for mining vary from 25 years to 60 years, depending on core assumptions such as the growth rate. Recycling is a major source of copper in the modern world. Because of these and other factors, the future of copper production and supply is the subject of much debate, including the concept of Peak copper, analogous to Peak Oil.

The price of copper has historically been unstable, and it quintupled from the 60-year low of US$0.60/lb (US$1.32/kg) in June 1999 to US$3.75 per pound (US$8.27/kg) in May 2006. It dropped to US$2.40/lb (US$5.29/kg) in February 2007, then rebounded to US$3.50/lb (US$7.71/kg) in April 2007. In February 2009, weakening global demand and a steep fall in commodity prices since the previous year's highs left copper prices at US$1.51/lb.

Methods

The concentration of copper in ores averages only 0.6%, and most commercial ores are sulfides, especially chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) and to a lesser extent chalcocite (Cu2S). These minerals are concentrated from crushed ores to the level of 10–15% copper by froth flotation or bioleaching. Heating this material with silica in flash smelting removes much of the iron as slag. The process exploits the greater ease of converting iron sulfides into its oxides, which in turn react with the silica to form the silicate slag, which floats on top of the heated mass. The resulting copper matte consisting of Cu2S is then roasted to convert all sulfides into oxides:

- 2 Cu2S + 3 O2 → 2 Cu2O + 2 SO2

The cuprous oxide is converted to blister copper upon heating:

- 2 Cu2O → 4 Cu + O2

The Sudbury matte process converted only half the sulfide to oxide and then used this oxide to remove the rest of the sulfur as oxide. It was then electrolytically refined and the anode mud exploited for the platinum and gold it contained. This step exploits the relatively easy reduction of copper oxides to copper metal. Natural gas is blown across the blister to remove most of the remaining oxygen and electrorefining is performed on the resulting material to produce pure copper:

- Cu2+ + 2 e– → Cu

Recycling

Copper, like aluminium, is 100% recyclable without any loss of quality whether in a raw state or contained in a manufactured product. In volume, copper is the third most recycled metal after iron and aluminium. It is estimated that 80% of the copper ever mined is still in use today. According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report, the global per capita stock of Copper in use in society is 35–55 kg. Much of this is in more-developed countries (140–300 kg per capita) rather than less-developed countries (30–40 kg per capita).

The process of recycling copper follows roughly the same steps as is used to extract copper, but requires fewer steps. High purity scrap copper is melted in a furnace and then reduced and cast into billets and ingots; lower purity scrap is refined by electroplating in a bath of sulfuric acid.

Alloys

Numerous copper alloys exist, many with important uses. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Bronze usually refers to copper-tin alloys, but can refer to any alloy of copper such as aluminium bronze. Copper is one of the most important constituents of carat silver and gold alloys and carat solders used in the jewelry industry, modifying the colour, hardness and melting point of the resulting alloys.

The alloy of copper and nickel, called cupronickel, is used in low-denomination statuary coins, often for the outer cladding. The US 5-cent coin called nickel consists of 75% copper and 25% nickel and has a homogeneous composition. The 90% copper/10% nickel alloy is remarkable by its resistance to corrosion and is used in various parts being exposed to seawater. Alloys of copper with aluminium (about 7%) have a pleasant golden colour and are used in decorations. Copper alloys with tin are part of lead-free solders.

Compounds

Binary compounds

As for other elements, the simplest compounds of copper are binary compounds, i.e. those containing only two elements. The principal ones are the oxides, sulfides and halides. Both cuprous and cupric oxides are known. Among the numerous copper sulfides, important examples include copper(I) sulfide and copper(II) sulfide.

The cuprous halides with chlorine, bromine, and iodine are known, as are the cupric halides with fluorine, chlorine, and bromine. Attempts to prepare copper(II) iodide give cuprous iodide and iodine.

- 2 Cu2+ + 4 I− → 2 CuI + I2

Coordination chemistry

Copper, like all metals, forms coordination complexes with ligands. In aqueous solution, copper(II) exists as [Cu(H2O)6]2+. This complex exhibits the fastest water exchange rate (speed of water ligands attaching and detaching) for any transition metal aquo complex. Adding aqueous sodium hydroxide causes the precipitation of light blue solid copper(II) hydroxide. A simplified equation is:

- Cu2+ + 2 OH− → Cu(OH)2

Aqueous ammonia results in the same precipitate. Upon adding excess ammonia, the precipitate dissolves, forming tetraamminecopper(II):

- Cu(H2O)4(OH)2 + 4 NH3 → [Cu(H2O)2(NH3)4]2+ + 2 H2O + 2 OH−

Many other oxyanions form complexes; these include copper(II) acetate, copper(II) nitrate, and copper(II) carbonate. Copper(II) sulfate forms a blue crystalline penta hydrate, which is the most familiar copper compound in the laboratory. It is used in a fungicide called the Bordeaux mixture.

Polyols, compounds containing more than one alcohol functional group, generally interact with cupric salts. For example, copper salts are used to test for reducing sugars. Specifically, using Benedict's reagent and Fehling's solution the presence of the sugar is signaled by a colour change from blue Cu(II) to reddish copper(I) oxide. Schweizer's reagent and related complexes with ethylenediamine and other amines dissolve cellulose. Amino acids form very stable chelate complexes with copper(II). Many wet-chemical tests for copper ions exist, one involving potassium ferrocyanide, which gives a brown precipitate with copper(II) salts.

Organocopper chemistry

Compounds that contain a carbon-copper bond are known as organocopper compounds. They are very reactive towards oxygen to form copper(I) oxide and have many uses in chemistry. They are synthesized by treating copper(I) compounds with Grignard reagents, terminal alkynes or organolithium reagents; in particular, the last reaction described produces a Gilman reagent. These can undergo substitution with alkyl halides to form coupling products; as such, they are important in the field of organic synthesis. Copper(I) acetylide is highly shock-sensitive but is an intermediate in reactions such as the Cadiot-Chodkiewicz coupling and the Sonogashira coupling. Conjugate addition to enones and carbocupration of alkynes can also be achieved with organocopper compounds. Copper(I) forms a variety of weak complexes with alkenes and carbon monoxide, especially in the presence of amine ligands.

Copper(III) and copper(IV)

Copper(III) is most characteristically found in oxides. A simple example is potassium cuprate, KCuO2, a blue-black solid. The best studied copper(III) compounds are the cuprate superconductors. Yttrium barium copper oxide (YBa2Cu3O7) consists of both Cu(II) and Cu(III) centres. Like oxide, fluoride is a highly basic anion and is known to stabilize metal ions in high oxidation states. Indeed, both copper(III) and even copper(IV) fluorides are known, K3CuF6 and Cs2CuF6, respectively.

Some copper proteins form oxo complexes, which also feature copper(III). With di- and tri peptides, purple-colored copper(III) complexes are stabilized by the deprotonated amide ligands.

Complexes of copper(III) are also observed as intermediates in reactions of organocopper compounds.

History

Copper Age

Copper occurs naturally as native copper and was known to some of the oldest civilizations on record. It has a history of use that is at least 10,000 years old, and estimates of its discovery place it at 9000 BC in the Middle East; a copper pendant was found in northern Iraq that dates to 8700 BC. There is evidence that gold and meteoric iron (but not iron smelting) were the only metals used by humans before copper. The history of copper metallurgy is thought to have followed the following sequence: 1) cold working of native copper, 2) annealing, 3) smelting, and 4) the lost wax method. In southeastern Anatolia, all four of these metallurgical techniques appears more or less simultaneously at the beginning of the Neolithic c. 7500 BC. However, just as agriculture was independently invented in several parts of the world (including Pakistan, China, and the Americas) copper smelting was invented locally in several different places. It was probably discovered independently in China before 2800 BC, in Central America perhaps around 600 AD, and in West Africa about the 9th or 10th century AD. Investment casting was invented in 4500–4000 BC in Southeast Asia and carbon dating has established mining at Alderley Edge in Cheshire, UK at 2280 to 1890 BC. Ötzi the Iceman, a male dated from 3300–3200 BC, was found with an axe with a copper head 99.7% pure; high levels of arsenic in his hair suggest his involvement in copper smelting. Experience with copper has assisted the development of other metals; in particular, copper smelting led to the discovery of iron smelting. Production in the Old Copper Complex in Michigan and Wisconsin is dated between 6000 and 3000 BC. Natural bronze, a type of copper made from ores rich in silicon, arsenic, and (rarely) tin, came into general use in the Balkans around 5500 BC. Previously the only tool made of copper had been the awl, used for punching holes in leather and gouging out peg-holes for wood joining. However, the introduction of a more robust form of copper led to the widespread use, and large-scale production of heavy metal tools, including axes, adzes, and axe-adzes.

Bronze Age

Alloying copper with tin to make bronze was first practiced about 4000 years after the discovery of copper smelting, and about 2000 years after "natural bronze" had come into general use. Bronze artifacts from Sumerian cities and Egyptian artifacts of copper and bronze alloys date to 3000 BC. The Bronze Age began in Southeastern Europe around 3700 - 3300 BC, in Northwestern Europe about 2500 BC. It ended with the beginning of the Iron Age, 2000-1000 BC in the Near East, 600 BC in Northern Europe. The transition between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age was formerly termed the Chalcolithic period (copper-stone), with copper tools being used with stone tools. This term has gradually fallen out of favour because in some parts of the world the Calcholithic and Neolithic are coterminous at both ends. Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is of much more recent origin. It was known to the Greeks, but became a significant supplement to bronze during the Roman Empire.

Antiquity and Middle Ages

In Greece, copper was known by the name chalkos (χαλκός). It was an important resource for the Romans, Greeks and other ancient peoples. In Roman times, it was known as aes Cyprium, aes being the generic Latin term for copper alloys and Cyprium from Cyprus, where much copper was mined. The phrase was simplified to cuprum, hence the English copper. Aphrodite and Venus represented copper in mythology and alchemy, because of its lustrous beauty, its ancient use in producing mirrors, and its association with Cyprus, which was sacred to the goddess. The seven heavenly bodies known to the ancients were associated with the seven metals known in antiquity, and Venus was assigned to copper.

Britain's first use of brass occurred around the 3rd–2nd century BC. In North America, copper mining began with marginal workings by Native Americans. Native copper is known to have been extracted from sites on Isle Royale with primitive stone tools between 800 and 1600. Copper metallurgy was flourishing in South America, particularly in Peru around 1000 AD; it proceeded at a much slower rate on other continents. Copper burial ornamentals from the 15th century have been uncovered, but the metal's commercial production did not start until the early 20th century.

The cultural role of copper has been important, particularly in currency. Romans in the 6th through 3rd centuries BC used copper lumps as money. At first, the copper itself was valued, but gradually the shape and look of the copper became more important. Julius Caesar had his own coins made from brass, while Octavianus Augustus Caesar's coins were made from Cu-Pb-Sn alloys. With an estimated annual output of around 15,000 t, Roman copper mining and smelting activities reached a scale unsurpassed until the time of the Industrial Revolution; the provinces most intensely mined were those of Hispania, Cyprus and in Central Europe.

The gates of the Temple of Jerusalem used Corinthian bronze made by depletion gilding. It was most prevalent in Alexandria, where alchemy is thought to have begun. In ancient India, copper was used in the holistic medical science Ayurveda for surgical instruments and other medical equipment. Ancient Egyptians (~2400 BC) used copper for sterilizing wounds and drinking water, and later on for headaches, burns, and itching. The Baghdad Battery, with copper cylinders soldered to lead, dates back to 248 BC to AD 226 and resembles a galvanic cell, leading people to believe this was the first battery; the claim has not been verified.

Modern period

The Great Copper Mountain was a mine in Falun, Sweden, that operated from the 10th century to 1992. It produced two thirds of Europe's copper demand in the 17th century and helped fund many of Sweden's wars during that time. It was referred to as the nation's treasury; Sweden had a copper backed currency.

The uses of copper in art were not limited to currency: it was used by Renaissance sculptors, in photographic technology known as the daguerreotype, and the Statue of Liberty. Copper plating and copper sheathing for ships' hulls was widespread; the ships of Christopher Columbus were among the earliest to have this feature. The Norddeutsche Affinerie in Hamburg was the first modern electroplating plant starting its production in 1876. The German scientist Gottfried Osann invented powder metallurgy in 1830 while determining the metal's atomic mass; around then it was discovered that the amount and type of alloying element (e.g., tin) to copper would affect bell tones. Flash smelting was developed by Outokumpu in Finland and first applied at Harjavalta in 1949; the energy-efficient process accounts for 50% of the world’s primary copper production.

The Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporting Countries, formed in 1967 with Chile, Peru, Zaire and Zambia, played a similar role for copper as OPEC does for oil. It never achieved the same influence, particularly because the second-largest producer, the United States, was never a member; it was dissolved in 1988.

Applications

The major applications of copper are in electrical wires (60%), roofing and plumbing (20%) and industrial machinery (15%). Copper is mostly used as a metal, but when a higher hardness is required it is combined with other elements to make an alloy (5% of total use) such as brass and bronze. A small part of copper supply is used in production of compounds for nutritional supplements and fungicides in agriculture. Machining of copper is possible, although it is usually necessary to use an alloy for intricate parts to get good machinability characteristics.

Wire and cable

Despite competition from other materials, copper remains the preferred electrical conductor in nearly all categories of electrical wiring with the major exception being overhead electric power transmission where aluminium is often preferred. Copper wire is used in power generation, power transmission, power distribution, telecommunications, electronics circuitry, and countless types of electrical equipment. Electrical wiring is the most important market for the copper industry. This includes building wire, communications cable, power distribution cable, appliance wire, automotive wire and cable, and magnet wire. Roughly half of all copper mined is used to manufacture electrical wire and cable conductors. Many electrical devices rely on copper wiring because of its multitude of inherent beneficial properties, such as its high electrical conductivity, tensile strength, ductility, creep (deformation) resistance, corrosion resistance, low thermal expansion, high thermal conductivity, solderability, and ease of installation.

Integrated circuits and printed circuit boards increasingly feature copper in place of aluminium because of its superior electrical conductivity (see Copper interconnect for main article); heat sinks and heat exchangers use copper as a result of its superior heat dissipation capacity to aluminium. Electromagnets, vacuum tubes, cathode ray tubes, and magnetrons in microwave ovens use copper, as do wave guides for microwave radiation.

Electric motors

Copper’s greater conductivity versus other metallic materials enhances the electrical energy efficiency of motors. This is important because motors and motor-driven systems account for 43%-46% of all global electricity consumption and 69% of all electricity used by industry. Increasing the mass and cross section of copper in a coil increases the electrical energy efficiency of the motor. Copper motor rotors, a new technology designed for motor applications where energy savings are prime design objectives, are enabling general-purpose induction motors to meet and exceed National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) premium efficiency standards.

Architecture

Copper has been used since ancient times as a durable, corrosion resistant, and weatherproof architectural material. Roofs, flashings, rain gutters, downspouts, domes, spires, vaults, and doors have been made from copper for hundreds or thousands of years. Copper’s architectural use has been expanded in modern times to include interior and exterior wall cladding, building expansion joints, radio frequency shielding, and antimicrobial indoor products, such as attractive handrails, bathroom fixtures, and counter tops. Some of copper’s other important benefits as an architectural material include its low thermal movement, light weight, lightning protection, and its recyclability.

The metal’s distinctive natural green patina has long been coveted by architects and designers. The final patina is a particularly durable layer that is highly resistant to atmospheric corrosion, thereby protecting the underlying metal against further weathering. It can be a mixture of carbonate and sulfate compounds in various amounts, depending upon environmental conditions such as sulfur-containing acid rain. Architectural copper and its alloys can also be 'finished' to embark a particular look, feel, and/or colour. Finishes include mechanical surface treatments, chemical coloring, and coatings.

Copper has excellent brazing and soldering properties and can be welded; the best results are obtained with gas metal arc welding.

Antibiofouling applications

Copper has long been used as a biostatic surface to line parts of ships to protect against barnacles and mussels. It was originally used pure, but has since been superseded by Muntz metal. Bacteria will not grow on a copper surface because it is biostatic. Similarly, as discussed in copper alloys in aquaculture, copper alloys have become important netting materials in the aquaculture industry because of the fact that they are antimicrobial and prevent biofouling, even in extreme conditions and have strong structural and corrosion-resistant properties in marine environments.

Antimicrobial applications

Numerous antimicrobial efficacy studies have been conducted in the past 10 years regarding copper’s efficacy to destroy a wide range of bacteria, as well as influenza A virus, adenovirus, and fungi.

Copper-alloy touch surfaces have natural intrinsic properties to destroy a wide range of microorganisms (e.g., E. coli O157:H7, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ( MRSA), Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile, influenza A virus, adenovirus, and fungi). Some 355 copper alloys were proven to kill more than 99.9% of disease-causing bacteria within just two hours when cleaned regularly. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved the registrations of these copper alloys as “ antimicrobial materials with public health benefits," which allows manufacturers to legally make claims as to the positive public health benefits of products made with registered antimicrobial copper alloys. In addition, the EPA has approved a long list of antimicrobial copper products made from these alloys, such as bedrails, handrails, over-bed tables, sinks, faucets, door knobs, toilet hardware, computer keyboards, health club equipment, shopping cart handles, etc. (for a comprehensive list of products, see: Antimicrobial copper-alloy touch surfaces#Approved products). Copper doorknobs are used by hospitals to reduce the transfer of disease, and Legionnaires' disease is suppressed by copper tubing in plumbing systems. Antimicrobial copper alloy products are now being installed in healthcare facilities in the U.K., Ireland, Japan, Korea, France, Denmark, and Brazil and in the subway transit system in Santiago, Chile, where copper-zinc alloy handrails will be installed in some 30 stations between 2011–2014.

Other uses

Copper compounds in liquid form are used as a wood preservative, particularly in treating original portion of structures during restoration of damage due to dry rot. Together with zinc, copper wires may be placed over non-conductive roofing materials to discourage the growth of moss. Textile fibers use copper to create antimicrobial protective fabrics, as do ceramic glazes, stained glass and musical instruments. Electroplating commonly uses copper as a base for other metals such as nickel.

Copper is one of three metals, along with lead and silver, used in a museum materials testing procedure called the Oddy test. In this procedure, copper is used to detect chlorides, oxides, and sulfur compounds.

Copper is also commonly found in jewelry, and folklore says that copper bracelets relieve arthritis symptoms, though this has been shown to be incorrect.

Copper oxide and carbonate is used in glassmaking and in ceramic glazes to impart green and brown colours.

Biological role

Copper proteins have diverse roles in biological electron transport and oxygen transportation, processes that exploit the easy interconversion of Cu(I) and Cu(II). The biological role for copper commenced with the appearance of oxygen in earth's atmosphere. The protein hemocyanin is the oxygen carrier in most mollusks and some arthropods such as the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus). Because hemocyanin is blue, these organisms have blue blood, not the red blood found in organisms that rely on hemoglobin for this purpose. Structurally related to hemocyanin are the laccases and tyrosinases. Instead of reversibly binding oxygen, these proteins hydroxylate substrates, illustrated by their role in the formation of lacquers.

Copper is also a component of other proteins associated with the processing of oxygen. In cytochrome c oxidase, which is required for aerobic respiration, copper and iron cooperate in the reduction of oxygen. Copper is also found in many superoxide dismutases, proteins that catalyze the decomposition of superoxides, by converting it (by disproportionation) to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide:

- 2 HO2 → H2O2 + O2

Several copper proteins, such as the "blue copper proteins", do not interact directly with substrates, hence they are not enzymes. These proteins relay electrons by the process called electron transfer.

Dietary needs

Copper is an essential trace element in plants and animals, but not some microorganisms. The human body contains copper at a level of about 1.4 to 2.1 mg per kg of body mass. Stated differently, the RDA for copper in normal healthy adults is quoted as 0.97 mg/day and as 3.0 mg/day. Copper is absorbed in the gut, then transported to the liver bound to albumin. After processing in the liver, copper is distributed to other tissues in a second phase. Copper transport here involves the protein ceruloplasmin, which carries the majority of copper in blood. Ceruloplasmin also carries copper that is excreted in milk, and is particularly well-absorbed as a copper source. Copper in the body normally undergoes enterohepatic circulation (about 5 mg a day, vs. about 1 mg per day absorbed in the diet and excreted from the body), and the body is able to excrete some excess copper, if needed, via bile, which carries some copper out of the liver that is not then reabsorbed by the intestine.

Copper-based disorders

Because of its role in facilitating iron uptake, copper deficiency can produce anaemia-like symptoms, neutropenia, bone abnormalities, hypopigmentation, impaired growth, increased incidence of infections, osteoporosis, hyperthyroidism, and abnormalities in glucose and cholesterol metabolism. Conversely, Wilson's disease causes an accumulation of copper in body tissues.

Severe deficiency can be found by testing for low plasma or serum copper levels, low ceruloplasmin, and low red blood cell superoxide dismutase levels; these are not sensitive to marginal copper status. The "cytochrome c oxidase activity of leucocytes and platelets" has been stated as another factor in deficiency, but the results have not been confirmed by replication.

Gram quantities of various copper salts have been taken in suicide attempts and produced acute copper toxicity in humans, possibly due to redox cycling and the generation of reactive oxygen species that damage DNA. Corresponding amounts of copper salts (30 mg/kg) are toxic in animals. A minimum dietary value for healthy growth in rabbits has been reported to be at least 3 ppm in the diet. However, higher concentrations of copper (100 ppm, 200 ppm, or 500 ppm) in the diet of rabbits may favorably influence feed conversion efficiency, growth rates, and carcass dressing percentages.

Chronic copper toxicity does not normally occur in humans because of transport systems that regulate absorption and excretion. Autosomal recessive mutations in copper transport proteins can disable these systems, leading to Wilson's disease with copper accumulation and cirrhosis of the liver in persons who have inherited two defective genes.