Poverty

Background Information

SOS Children, which runs nearly 200 sos schools in the developing world, organised this selection. Before you decide about sponsoring a child, why not learn about different sponsorship charities first?

Poverty is the state of one who lacks a certain amount of material possessions or money. Absolute poverty or destitution refers to the deprivation of basic human needs, which commonly includes food, water, sanitation, clothing, shelter, health care and education. Relative poverty is defined contextually as economic inequality in the location or society in which people live.

For much of history, poverty was considered largely unavoidable as traditional modes of production were insufficient to give an entire population a comfortable standard of living. After the industrial revolution, mass production in factories made wealth increasingly more inexpensive and accessible. Of more importance is the modernization of agriculture, such as fertilizers, in order to provide enough yield to feed the population. The supply of basic needs can be restricted by constraints on government services such as corruption, illicit capital flight, debt and loan conditionalities and by the brain drain of health care and educational professionals. Strategies of increasing income to make basic needs more affordable typically include welfare, economic freedom, and providing financial services.

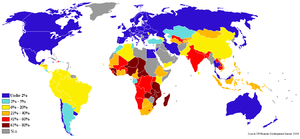

Poverty reduction is a major goal and issue for many international organizations such as the United Nations and the World Bank. The World Bank estimated 1.29 billion people were living in absolute poverty in 2008. Of these, about 400 million people in absolute poverty lived in India and 173 million people in China. In terms of percentage of regional populations, sub-Saharan Africa at 47% had the highest incidence rate of absolute poverty in 2008. Between 1990 and 2010, about 663 million people moved above the absolute poverty level. Still, extreme poverty is a global challenge; it is observed in all parts of the world, including the developed economies.

Etymology

The word poverty comes from old French poverté (Modern French: pauvreté), from Latin paupertās, from pauper (poor).

The English word "poverty" via Anglo-Norman povert. There are several definitions of poverty depending on the context of the situation in is placed in and the views of the person giving the definition.

Measuring poverty

Definitions

United Nations: Fundamentally, poverty is a denial of choices and opportunities, a violation of human dignity. It means lack of basic capacity to participate effectively in society. It means not having enough to feed and clothe a family, not having a school or clinic to go to, not having the land on which to grow one’s food or a job to earn one’s living, not having access to credit. It means insecurity, powerlessness and exclusion of individuals, households and communities. It means susceptibility to violence, and it often implies living in marginal or fragile environments, without access to clean water or sanitation.

World Bank: Poverty is pronounced deprivation in well-being, and comprises many dimensions. It includes low incomes and the inability to acquire the basic goods and services necessary for survival with dignity. Poverty also encompasses low levels of health and education, poor access to clean water and sanitation, inadequate physical security, lack of voice, and insufficient capacity and opportunity to better one’s life.

Copenhagen Declaration: Absolute poverty is a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only on income but also on access to social services. The term 'absolute poverty' is sometimes synonymously referred to as 'extreme poverty.'

Absolute poverty

Poverty is usually measured as either absolute or relative (the latter being actually an index of income inequality). Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries.

For a few years starting 1990, The World Bank anchored absolute poverty line as $1 per day. This was revised in 1993, and through 2005, absolute poverty was $1.08 a day for all countries on a purchasing power parity basis, after adjusting for inflation to the 1993 U.S. dollar. In 2005, after extensive studies of cost of living across the world, The World Bank raised the measure for global poverty line to reflect the observed higher cost of living. Now, the World Bank defines extreme poverty as living on less than US$1.25 ( PPP) per day, and moderate poverty as less than $2 or $5 a day (but note that a person or family with access to subsistence resources, e.g. subsistence farmers, may have a low cash income without a correspondingly low standard of living – they are not living "on" their cash income but using it as a top up). It estimates that "in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day." A dollar a day, in nations that do not use the U.S. dollar as currency, does not translate to living a day on the equivalent amount of local currency as determined by the exchange rate. Rather, it is determined by the purchasing power parity rate, which would look at how much local currency is needed to buy the same things that a dollar could buy in the United States. Usually, this would translate to less local currency than the exchange rate in poorer countries as the United States is a relatively more expensive country.

The poverty line threshold of $1.25 per day, as set by The World Bank, is controversial. Each nation has its own threshold for absolute poverty line; in the United States, for example, the absolute poverty line was US$15.15 per day in 2010 (US$22,000 per year for a family of four), while in India it was US$ 1.0 per day and in China the absolute poverty line was US$ 0.55 per day, each on PPP basis in 2010. These different poverty lines make data comparison between each nation's official reports qualitatively difficult. Some scholars argue that The World Bank method sets the bar too high, others argue it is low. Still others suggest that poverty line misleads as it measures everyone below the poverty line the same, when in reality someone living on $1.2 per day is in a different state of poverty than someone living on $0.2 per day. In other words, the depth and intensity of poverty varies across the world and in any regional populations, and $1.25 per day poverty line and head counts are inadequate measures.

The proportion of the developing world's population living in extreme economic poverty fell from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001. Most of this improvement has occurred in East and South Asia. In East Asia the World Bank reported that "The poverty headcount rate at the $2-a-day level is estimated to have fallen to about 27 percent [in 2007], down from 29.5 percent in 2006 and 69 percent in 1990." In Sub-Saharan Africa extreme poverty went up from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001, which combined with growing population increased the number of people living in extreme poverty from 231 million to 318 million.

In the early 1990s some of the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income. The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in large declines in GDP per capita, of about 30 to 35% between 1990 and the trough year of 1998 (when it was at its minimum). As a result poverty rates also increased although in subsequent years as per capita incomes recovered the poverty rate dropped from 31.4% of the population to 19.6%

World Bank data shows that the percentage of the population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line has decreased in each region of the world since 1990:

| Region | $1 per day | $1.25 per day | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2002 | 2004 | 1981 | 2008 | ||

| East Asia and Pacific | 15.40% | 12.33% | 9.07% | 77.2% | 14.3% | |

| Europe and Central Asia | 3.60% | 1.28% | 0.95% | 1.9% | 0.5% | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 9.62% | 9.08% | 8.64% | 11.9% | 6.5% | |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2.08% | 1.69% | 1.47% | 9.6% | 2.7% | |

| South Asia | 35.04% | 33.44% | 30.84% | 61.1% | 36% | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46.07% | 42.63% | 41.09% | 51.5% | 47.5% | |

| World | 52.2% | 22.4% | ||||

According to Chen and Ravallion, about 1.76 billion people in developing world lived above $1.25 per day and 1.9 billion people lived below $1.25 per day in 1981. The world's population increased over the next 25 years. In 2005, about 4.09 billion people in developing world lived above $1.25 per day and 1.4 billion people lived below $1.25 per day (both 1981 and 2005 data are on inflation adjusted basis). Some scholars caution that these trends are subject to various assumptions, and not certain. Additionally, they note that the poverty reduction is not uniform across the world; economically prospering countries such as China, India and Brazil have made more progress in absolute poverty reduction than countries in other regions of the world.

The absolute poverty measure trends noted above are supported by human development indicators, which have also been improving. Life expectancy has greatly increased in the developing world since World War II and is starting to close the gap to the developed world. Child mortality has decreased in every developing region of the world. The proportion of the world's population living in countries where per-capita food supplies are less than 2,200 calories (9,200 kilojoules) per day decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Similar trends can be observed for literacy, access to clean water and electricity and basic consumer items.

Relative poverty

Relative poverty views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context, hence relative poverty is a measure of income inequality. Usually, relative poverty is measured as the percentage of population with income less than some fixed proportion of median income. There are several other different income inequality metrics, for example the Gini coefficient or the Theil Index.

Relative poverty measures are used as official poverty rates in several developed countries. As such these poverty statistics measure inequality rather than material deprivation or hardship. The measurements are usually based on a person's yearly income and frequently take no account of total wealth. The main poverty line used in the OECD and the European Union is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 60% of the median household income.

Mobility

Poverty levels are snapshot picture in time that omits the transitional dynamics between levels. Mobility statistics supply additional information about the fraction who leave the poverty level. For example, one study finds that in a sixteen-year period (1975 to 1991 in the U.S.) only 5% of those in the lower fifth of the income level were still in that level, while 95% transitioned to a higher income category. Poverty levels can remain the same while those who rise out of poverty are replaced by others. The transient poor and chronic poor differ in each society. In a nine-year period ending in 2005 for the U.S., 50% of the poorest quintile transitioned to a higher quintile.

Other aspects

Economic aspects of poverty focus on material needs, typically including the necessities of daily living, such as food, clothing, shelter, or safe drinking water. Poverty in this sense may be understood as a condition in which a person or community is lacking in the basic needs for a minimum standard of well-being and life, particularly as a result of a persistent lack of income.

Analysis of social aspects of poverty links conditions of scarcity to aspects of the distribution of resources and power in a society and recognizes that poverty may be a function of the diminished "capability" of people to live the kinds of lives they value. The social aspects of poverty may include lack of access to information, education, health care, or political power.

Poverty may also be understood as an aspect of unequal social status and inequitable social relationships, experienced as social exclusion, dependency, and diminished capacity to participate, or to develop meaningful connections with other people in society. Such social exclusion can be minimized through strengthened connections with the mainstream, such as through the provision of relational care to those who are experiencing poverty.

The World Bank's "Voices of the Poor," based on research with over 20,000 poor people in 23 countries, identifies a range of factors which poor people identify as part of poverty. These include:

- Precarious livelihoods

- Excluded locations

- Physical limitations

- Gender relationships

- Problems in social relationships

- Lack of security

- Abuse by those in power

- Dis-empowering institutions

- Limited capabilities

- Weak community organizations

David Moore, in his book The World Bank, argues that some analysis of poverty reflect pejorative, sometimes racial, stereotypes of impoverished people as powerless victims and passive recipients of aid programs.

Ultra-poverty, a term apparently coined by Michael Lipton, connotes being amongst poorest of the poor in low-income countries. Lipton defined ultra-poverty as receiving less than 80 percent of minimum caloric intake whilst spending more than 80% of income on food. Alternatively a 2007 report issued by International Food Policy Research Institute defined ultra-poverty as living on less than 54 cents per day.

Asset poverty is an economic and social condition that is more persistent and prevalent than income poverty. It can be defined as a household’s inability to access wealth resources that are sufficient enough to provide for basic needs for a period of three months. Basic needs refer to the minimum standards for consumption and acceptable needs.[1] Wealth resources consist of home ownership, other real estate (second home, rented properties, etc.), net value of farm and business assets, stocks, checking and savings accounts, and other savings (money in savings bonds, life insurance policy cash values, etc.).[2] Wealth is measured in three forms: net worth, net worth minus home equity, and liquid assets. Net worth consists of all the aspects mentioned above. Net worth minus home equity is the same except it does not include home ownership in asset calculations. Liquid assets are resources that are readily available such as cash, checking and savings accounts, stocks, and other sources of savings.[2] There are two types of assets: tangible and intangible. Tangible assets most closely resemble liquid assets in that they include stocks, bonds, property, natural resources, and hard assets not in the form of real estate. Intangible assets are simply the access to credit, social capital, cultural capital, political capital, and human capital.

Characteristics

The effects of poverty may also be causes, as listed above, thus creating a "poverty cycle" operating across multiple levels, individual, local, national and global.

Health

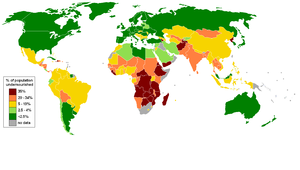

One third of deaths – some 18 million people a year or 50,000 per day – are due to poverty-related causes: in total 270 million people, most of them women and children, have died as a result of poverty since 1990. Those living in poverty suffer disproportionately from hunger or even starvation and disease. Those living in poverty suffer lower life expectancy. According to the World Health Organization, hunger and malnutrition are the single gravest threats to the world's public health and malnutrition is by far the biggest contributor to child mortality, present in half of all cases. Almost 90% of maternal deaths during childbirth occur in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, compared to less than 1% in the developed world.

Those who live in poverty have also been shown to have a far greater likelihood of having or incurring a disability within their lifetime. Infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis can perpetuate poverty by diverting health and economic resources from investment and productivity; malaria decreases GDP growth by up to 1.3% in some developing nations and AIDS decreases African growth by 0.3–1.5% annually.

Hunger

Rises in the costs of living making poor people less able to afford items. Poor people spend a greater portion of their budgets on food than richer people. As a result, poor households and those near the poverty threshold can be particularly vulnerable to increases in food prices. For example, in late 2007 increases in the price of grains led to food riots in some countries. The World Bank warned that 100 million people were at risk of sinking deeper into poverty. Threats to the supply of food may also be caused by drought and the water crisis. Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and decline of agricultural yields. Approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded. In Africa, if current trends of soil degradation continue, the continent might be able to feed just 25% of its population by 2025, according to United Nations University's Ghana-based Institute for Natural Resources in Africa. Every year nearly 11 million children living in poverty die before their fifth birthday. 1.02 billion people go to bed hungry every night.

According to the Global Hunger Index, Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest child malnutrition rate of the world's regions over the 2001-2006 period.

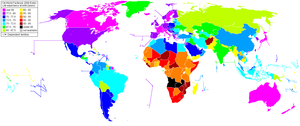

Education

Research has found that there is a high risk of educational underachievement for children who are from low-income housing circumstances. This often is a process that begins in primary school for some less fortunate children. Instruction in the US educational system, as well as in most other countries, tends to be geared towards those students who come from more advantaged backgrounds. As a result, children in poverty are at a higher risk than advantaged children for retention in their grade, special deleterious placements during the school's hours and even not completing their high school education. There are indeed many explanations for why students tend to drop out of school. One is the conditions of which they attend school. Schools in poverty-stricken areas have conditions that hinder children from learning in a safe environment. Researchers have developed a name for areas like this: urban war zone is a poor, crime-laden district in which deteriorated, violent, even war-like conditions and underfunded, largely ineffective schools promote inferior academic performance, including irregular attendance and disruptive or non-compliant classroom behaviour. For children with low resources, the risk factors are similar to others such as juvenile delinquency rates, higher levels of teenage pregnancy, and the economic dependency upon their low income parent or parents. Families and society who submit low levels of investment in the education and development of less fortunate children end up with less favorable results for the children who see a life of parental employment reduction and low wages. Higher rates of early childbearing with all the connected risks to family, health and well-being are major important issues to address since education from preschool to high school are both identifiably meaningful in a life.

Poverty often drastically affects children's success in school. A child's "home activities, preferences, mannerisms" must align with the world and in the cases that they do not these students are at a disadvantage in the school and most importantly the classroom. Therefore, it is safe to state that children who live at or below the poverty level will have far less success educationally than children who live above the poverty line. Poor children have a great deal less healthcare and this ultimately results in many absences from the academic year. Additionally, poor children are much more likely to suffer from hunger, fatigue, irritability, headaches, ear infections, flu, and colds. These illnesses could potentially restrict a child or student's focus and concentration.

Harmful spending habits mean that the poor typically spend about 2 percent of their income educating their children but larger percentages on alcohol and tobacco (For example, 6 percent in Indonesia and 8 percent in Mexico).

Housing and utilities

Poverty increases the risk of homelessness. Slum-dwellers, who make up a third of the world's urban population, live in a poverty no better, if not worse, than rural people, who are the traditional focus of the poverty in the developing world, according to a report by the United Nations. There are over 100 million street children worldwide. Most of the children living in institutions around the world have a surviving parent or close relative, and they most commonly entered orphanages because of poverty. Experts and child advocates maintain that orphanages are expensive and often harm children's development by separating them from their families. It is speculated that, flush with money, orphanages are increasing and push for children to join even though demographic data show that even the poorest extended families usually take in children whose parents have died.

Because of poor targeting of utility water subsidies, only 30%, on average, of the supplying costs in developing countries is covered. Lack of incentive to maintain delivery systems lead to the loss from leaks annually that is enough for 200 million people. Lack of incentive to expand delivery means the poor have to pay about five to 16 times the metered price.

The poorest fifth receive 0.1% of the world’s lighting but pay a fifth of total spending on light, accounting for 25 to 30 percent of their income. Indoor air pollution from burning fuels kills 2 million, almost half the deaths are from pneumonia in children under 5. Fuel from Bamboo burns more cleanly and also matures much faster than wood, thus reducing deforestation. Additionally, the use of solar panels are cheaper over their lifetime.

Violence

According to experts, many women become victims of trafficking, the most common form of which is prostitution, as a means of survival and economic desperation. Deterioration of living conditions can often compel children to abandon school in order to contribute to the family income, putting them at risk of being exploited. For example, in Zimbabwe, a number of girls are turning to prostitution for food to survive because of the increasing poverty.

In one survey, 67% of children from disadvantaged inner cities said they had witnessed a serious assault, and 33% reported witnessing a homicide. 51% of fifth graders from New Orleans (median income for a household: $27,133) have been found to be victims of violence, compared to 32% in Washington, DC (mean income for a household: $40,127).

Poverty reduction

Various poverty reduction strategies are broadly categorized here based on whether they make more of the basic human needs available or increase the disposable income needed to purchase those needs. Some strategies such as building roads can both bring access to various basic needs, such as fertilizer or healthcare from urban areas, as well as increase incomes, by bringing better access to urban markets.

Increasing the supply of basic needs

Food and other goods

Agricultural technologies such as nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides and new irrigation methods have dramatically reduced food shortages in modern times by boosting yields past previous constraints.

Before the Industrial Revolution, poverty had been mostly accepted as inevitable as economies produced little, making wealth scarce. Geoffrey Parker wrote that "In Antwerp and Lyon, two of the largest cities in western Europe, by 1600 three-quarters of the total population were too poor to pay taxes, and therefore likely to need relief in times of crisis." The initial industrial revolution led to high economic growth and eliminated mass absolute poverty in what is now considered the developed world. Mass production of goods in places such as rapidly industrializing China has made what were once considered luxuries, such as vehicles and computers, inexpensive and thus accessible to many who were otherwise too poor to afford them.

Even with new products, such as better seeds, or greater volumes of them, such as industrial production, the poor still require access to these products. Improving road and transportation infrastructure helps solve this major bottleneck. In Africa, it costs more to move fertilizer from an African seaport 60 miles inland than to ship it from the United States to Africa because of sparse, low quality roads, leading to fertilizer costs two to six times the world average. Microfranchising models such as door to door businesses are used to sell basic needs to remote areas for below market prices.

Health care and education

Nations do not necessarily need wealth to gain health. For example, Sri Lanka had a maternal mortality rate of 2% in the 1930s, higher than any nation today. It reduced it to 0.5–0.6% in the 1950s and to .06% today while spending less each year on maternal health because it learned what worked and what did not. Cheap water filters and promoting hand washing are some of the most cost effective health interventions and can cut deaths from diarrhea and pneumonia. Knowledge on the cost effectiveness of healthcare interventions can be elusive and educational measures have been made to disseminate what works, such as the Copenhagen Consensus.

Strategies to provide education cost effectively include deworming children, which costs about 50 cents per child per year and reduces non-attendance from anaemia, illness and malnutrition, while being only a twenty-fifth as expensive as increasing school attendance by constructing schools. Schoolgirl absenteeism could be cut in half by simply providing free sanitary towels.

Desirable actions such as enrolling children in school or receiving vaccinations can be encouraged by a form of aid known as conditional cash transfers. In Mexico, for example, dropout rates of 16- to 19-year-olds in rural area dropped by 20% and children gained half an inch in height. Initial fears that the program would encourage families to stay at home rather than work to collect benefits have proven to be unfounded. Instead, there is less excuse for neglectful behaviour as, for example, children stopped begging on the streets instead of going to school because it could result in suspension from the program.

Removing constraints on government services

Government revenue can be diverted away from basic services by corruption. Funds from aid and natural resources are often sent by government individuals for money laundering to overseas banks which insist on bank secrecy, instead of spending on the poor. A Global Witness report asked for more action from Western banks as they have proved capable of stanching the flow of funds linked to terrorism.

Illicit capital flight from the developing world is estimated at ten times the size of aid it receives and twice the debt service it pays. About 60 per cent of illicit capital flight from Africa is from transfer mispricing, where a subsidiary in a developing nation sells to another subsidiary or shell company in a tax haven at an artificially low price in order to pay less tax. An African Union report estimates that about 30% of sub-Saharan Africa's GDP has been moved to tax havens. Solutions include corporate “country-by-country reporting” where corporations disclose activities in each country and thereby prohibit the use of tax havens where no effective economic activity occurs.

Developing countries' debt service to banks and governments from richer countries can constrain government spending on the poor. For example, Zambia spent 40% of its total budget to repay foreign debt, and only 7% for basic state services in 1997. One of the proposed ways to help poor countries has been debt relief. Zambia began offering services, such as free health care even while overwhelming the health care infrastructure, because of savings that resulted from a 2005 round of debt relief.

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as primary holders of developing countries' debt, attach structural adjustment conditionalities in return for loans which generally include the elimination of state subsidies and the privatization of state services. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer even while many farmers cannot afford them at market prices. In Malawi, almost five million of its 13 million people used to need emergency food aid but after the government changed policy and subsidies for fertilizer and seed were introduced, farmers produced record-breaking corn harvests in 2006 and 2007 as Malawi became a major food exporter.

A major proportion of aid from donor nations is tied, mandating that a receiving nation spend on products and expertise originating only from the donor country. US law requires food aid be spent on buying food at home, instead of where the hungry live, and, as a result, half of what is spent is used on transport.

Reversing brain drain

The loss of basic needs providers emigrating from impoverished countries has a damaging effect. For example, an estimated 100,000 Philippine nurses emigrated between 1994 and 2006. As of 2004, there were more Ethiopia-trained doctors living in Chicago than in Ethiopia. Proposals to mitigate the problem by the World Health Organization include compulsory government service for graduates of public medical and nursing schools and creating career-advancing programs to retain personnel.

Controlling overpopulation

Some argue that overpopulation and lack of access to birth control leads to population increase to exceed food production and other resources. Empowering women with better education and more control of their lives makes them more successful in bringing down rapid population growth because they have more say in family planning.

Increasing personal income

The following are strategies used or proposed to increase personal incomes among the poor. Raising farm incomes is described as the core of the antipoverty effort as three quarters of the poor today are farmers. Estimates show that growth in the agricultural productivity of small farmers is, on average, at least twice as effective in benefiting the poorest half of a country’s population as growth generated in nonagricultural sectors.

Income grants

A guaranteed minimum income ensures that every citizen will live be able to purchase a desired level of basic needs. A more specific policy, called a basic income (or negative income tax) is a system of social security, that periodically provides each citizen, rich or poor, with a sum of money that is sufficient to live on. Studies of large cash-transfer programs in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Malawi show that the programs can be effective in increasing consumption, schooling, and nutrition, whether they are tied to such conditions or not. Proponents argue that a basic income is more economically efficient than a minimum wage and unemployment benefits, as the minimum wage effectively imposes a high marginal tax on employers, causing losses in efficiency. In 1968, Paul Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith and another 1,200 economists signed a document calling for the US Congress to introduce a system of income guarantees. Winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, with often diverse political convictions, who support a basic income include Herbert A. Simon, Friedrich Hayek, Robert Solow, Milton Friedman, Jan Tinbergen, James Tobin and James Meade.

Income grants are argued to be vastly more efficient in extending basic needs to the poor than in-kind subsidies. In some countries, fuel subsidies are a larger part of the budget than health and education. Additionally, most of the beneficiaries of in-kind subsidies are those who are not poor, such as by those who consume the same subsidized fuel, thus hampering the subsidies' effectiveness . A 2008 study concluded that the money spent on in-kind transfers in India in a year could lift all India’s poor out of poverty for that year if transferred directly. Similarly, the famine relief model increasing used by aid groups calls for giving cash or cash vouchers to the hungry to pay local farmers instead of buying food from donor countries, often required by law, as it wastes money on transport costs.

Economic freedoms

In Canada, it takes two days, two registration procedures, and $280 to open a business, while an entrepreneur in Bolivia must pay $2,696 in fees, wait 82 business days, and go through 20 procedures to do the same. Such costly barriers favour big firms at the expense of small enterprises, where most jobs are created. Often, businesses have to bribe government officials even for routine activities, which is, in effect, a tax on business. Noted reductions in poverty in recent decades has occurred in China and India mostly as a result of the abandonment of collective farming in China and the ending of the central planning model known as the License Raj in India, where GDP grew slower in the 1970s than the preceding 100 years. The World Bank concludes that governments and feudal elites extending to the poor the right to the land that they live and use is ‘the key to reducing poverty’ citing that land rights greatly increase poor people’s wealth, in some cases doubling it. Although approaches varied, the World Bank said the key issues were security of tenure and ensuring land transactions costs were low.

Greater access to markets brings more income to the poor. Road infrastructure has a direct impact on poverty. According to the World Bank, migration from poorer countries resulted in $328 billion sent from richer to poorer countries in 2010, more than double the $120 billion in official aid flows from OECD members. In 2011, India got $52 billion from its diaspora, more than it took in foreign direct investment.

Financial services

Microloans, made famous by the Grameen Bank, is where small amounts of money are loaned to farmers or villages, mostly women, who can then obtain physical capital to increase their economic rewards. However, microlending has been criticized for making hyperprofits off the poor even from its founder, Muhammad Yunus, and in India, which has seen a growing wave of defaults and suicides.

Those in poverty place overwhelming importance on having a safe place to save money, much more so than receiving loans. Also, a large part of microfinance loans are spent on products that would usually be paid by a checking or savings account. Lack of financial services, as a result of restrictive regulations, such as the requirements for banking licenses, makes it hard for even smaller microsavings programs to reach the poor. Mobile banking utilizes the wide availability of mobile phones to address the problem of the heavy regulation and costly maintenance of saving accounts. Safaricom’s M-Pesa launched one of the first systems where a network of agents of mostly shopkeepers, instead of bank branches, would take deposits in cash and translate these onto a virtual account on customers' phones. Cash transfers can be done between phones and issued back in cash with a small commission, making remittances safer.

Cultural factors to productivity

Cultural factors, such as discrimination of various kinds, can negatively affect productivity such as age discrimination, stereotyping, gender discrimination, racial discrimination, and caste discrimination. Max Weber and the modernization theory suggest that cultural values could affect economic success. However, researchers have gathered evidence that suggest that values are not as deeply ingrained and that changing economic opportunities explain most of the movement into and out of poverty, as opposed to shifts in values.

Voluntary poverty

Among some individuals, poverty is considered a necessary or desirable condition, which must be embraced to reach certain spiritual, moral, or intellectual states. Poverty is often understood to be an essential element of renunciation in religions such as Buddhism (only for monks, not for lay persons) and Jainism, whilst in Roman Catholicism it is one of the evangelical counsels. Calling this poverty would be a biggest mistake, as the main principle of Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism or Gandhi's teaching is to use minimum resources or giving up the greed to consume. The main aim of giving up materialistic world is to withdraw oneself from sensual pleasures (as they are fake and temporary as per these religions). This self-invited poverty (or giving up pleasures) is different than the one resulted due to economic imbalance.

Benedict XVI distinguishes “poverty chosen” (the poverty of spirit proposed by Jesus), and “poverty to be fought” (unjust and imposed poverty). He considers that the moderation implied in the former favors solidarity, and is a necessary condition so as to fight effectively to eradicate the abuse of the latter.