Binomial coefficient

Did you know...

This selection is made for schools by a children's charity read more. SOS Children is the world's largest charity giving orphaned and abandoned children the chance of family life.

In mathematics, particularly in combinatorics, a binomial coefficient is a coefficient of any of the terms in the expansion of the binomial (x+y)n. Colloquially given, say there are n pizza toppings to select from, if one wishes to bake a pizza with exactly k different toppings, then the binomial coefficient expresses how many different types of such k-topping pizzas are possible.

Definition

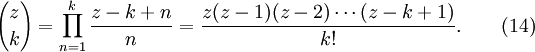

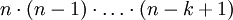

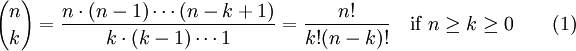

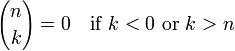

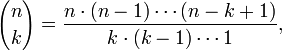

Given a non-negative integer n and an integer k, the binomial coefficient is defined to be the natural number

and

where n! denotes the factorial of n.

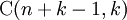

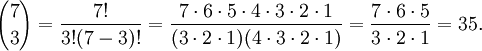

According to Nicholas J. Higham, the  notation was introduced by Albert von Ettinghausen in 1826, although these numbers were already known centuries before that (see Pascal's triangle). Alternative notations include C(n, k), nCk or

notation was introduced by Albert von Ettinghausen in 1826, although these numbers were already known centuries before that (see Pascal's triangle). Alternative notations include C(n, k), nCk or  , in all of which the C stands for combination or choose. Indeed, another name for the binomial coefficient is choose function, and the binomial coefficient of n and k is often read as "n choose k".

, in all of which the C stands for combination or choose. Indeed, another name for the binomial coefficient is choose function, and the binomial coefficient of n and k is often read as "n choose k".

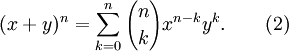

The binomial coefficients are the coefficients in the expansion of the binomial (x + y)n (hence the name):

This is generalized by the binomial theorem, which allows the exponent n to be negative or a non-integer. See the article on combination.

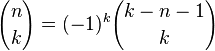

Combinatorial interpretation

The importance of the binomial coefficients (and the motivation for the alternate name 'choose') lies in the fact that  is the number of ways that k objects can be chosen from among n objects, regardless of order. More formally,

is the number of ways that k objects can be chosen from among n objects, regardless of order. More formally,

is the number of k-element subsets of an n-element set.

is the number of k-element subsets of an n-element set.

In fact, this property is often chosen as an alternative definition of the binomial coefficient, since from (1a) one may derive (1) as a corollary by a straightforward combinatorial proof. For a colloquial demonstration, note that in the formula

the numerator gives the number of ways to fill the k slots using the n options, where the slots are distinguishable from one another. Thus a pizza with mushrooms added before chicken is considered to be different from a pizza with chicken added before mushrooms. The denominator eliminates these repetitions because if the k slots are indistinguishable, then all of the k! ways of arranging them are considered identical.

On the context of computer science, it also helps to see  as the number of strings consisting of ones and zeros with k ones and n−k zeros. For each k-element subset, K, of an n-element set, N, the indicator function, 1K : N->{0,1}, where 1K(x) = 1 whenever x in K and 0 otherwise, produces a unique bit string of length n with exactly k ones by feeding 1K with the n elements in a specific order.

as the number of strings consisting of ones and zeros with k ones and n−k zeros. For each k-element subset, K, of an n-element set, N, the indicator function, 1K : N->{0,1}, where 1K(x) = 1 whenever x in K and 0 otherwise, produces a unique bit string of length n with exactly k ones by feeding 1K with the n elements in a specific order.

Example

The calculation of the binomial coefficient is conveniently arranged like this: ((((5/1)·6)/2)·7)/3, alternately dividing and multiplying with increasing integers. Each division produces an integer result which is itself a binomial coefficient.

Derivation from binomial expansion

For exponent 1, (x+y)1 is x+y. For exponent 2, (x+y)2 is (x+y)(x+y), which forms terms as follows. The first factor supplies either an x or a y; likewise for the second factor. Thus to form x2, the only possibility is to choose x from both factors; likewise for y2. However, the xy term can be formed by x from the first and y from the second factor, or y from the first and x from the second factor; thus it acquires a coefficient of 2. Proceeding to exponent 3, (x+y)3 reduces to (x+y)2(x+y), where we already know that (x+y)2= x2+2xy+y2, giving an initial expansion of (x+y)(x2+2xy+y2). Again the extremes, x3 and y3 arise in a unique way. However, the x2y term is either 2xy times x or x2 times y, for a coefficient of 3; likewise xy2 arises in two ways, summing the coefficients 1 and 2 to give 3.

This suggests an induction. Thus for exponent n, each term has total degree (sum of exponents) n, with n−k factors of x and k factors of y. If k is 0 or n, the term arises in only one way, and we get the terms xn and yn. If k is neither 0 nor n, then the term arises in two ways, from xn-k-1yk × x and from xn-kyk-1 × y. For example, x2y2 is both xy2 times x and x2y times y, thus its coefficient is 3 (the coefficient of xy2) + 3 (the coefficient of x2y). This is the origin of Pascal's triangle, discussed below.

Another perspective is that to form xn−kyk from n factors of (x+y), we must choose y from k of the factors and x from the rest. To count the possibilities, consider all n! permutations of the factors. Represent each permutation as a shuffled list of the numbers from 1 to n. Select an x from the first n−k factors listed, and a y from the remaining k factors; in this way each permutation contributes to the term xn−kyk. For example, the list 〈4,1,2,3〉 selects x from factors 4 and 1, and selects y from factors 2 and 3, as one way to form the term x2y2.

- (x +1 y)(x +2 y)(x +3 y)(x +4 y)

But the distinct list 〈1,4,3,2〉 makes exactly the same selection; the binomial coefficient formula must remove this redundancy. The n−k factors for x have (n−k)! permutations, and the k factors for y have k! permutations. Therefore n!/(n−k)!k! is the number of truly distinct ways to form the term xn−kyk.

A simpler explanation follows: One can pick a random element out of  in exactly

in exactly  ways, a second random element in

ways, a second random element in  ways, and so forth. Thus,

ways, and so forth. Thus,  elements can be picked out of n in

elements can be picked out of n in  ways. In this calculation, however, each order-independent selection occurs

ways. In this calculation, however, each order-independent selection occurs  times, as a list of

times, as a list of  elements can be permuted in so many ways. Thus eq. (1) is obtained.

elements can be permuted in so many ways. Thus eq. (1) is obtained.

Pascal's triangle

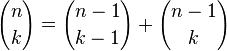

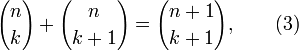

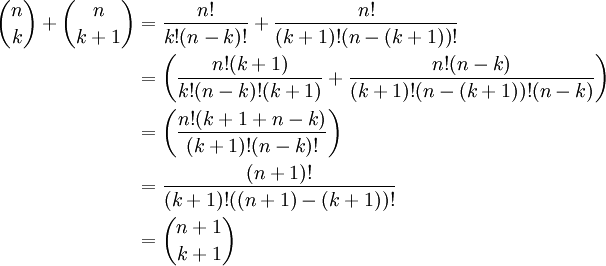

Pascal's rule is the important recurrence relation

which follows directly from the definition:

The recurrence relation just proved can be used to prove by mathematical induction that C(n, k) is a natural number for all n and k, a fact that is not immediately obvious from the definition.

Pascal's rule also gives rise to Pascal's triangle:

-

0: 1 1: 1 1 2: 1 2 1 3: 1 3 3 1 4: 1 4 6 4 1 5: 1 5 10 10 5 1 6: 1 6 15 20 15 6 1 7: 1 7 21 35 35 21 7 1 8: 1 8 28 56 70 56 28 8 1

Row number n contains the numbers C(n, k) for k = 0,…,n. It is constructed by starting with ones at the outside and then always adding two adjacent numbers and writing the sum directly underneath. This method allows the quick calculation of binomial coefficients without the need for fractions or multiplications. For instance, by looking at row number 5 of the triangle, one can quickly read off that

- (x + y)5 = 1 x5 + 5 x4y + 10 x3y2 + 10 x2y3 + 5 x y4 + 1 y5.

The differences between elements on other diagonals are the elements in the previous diagonal, as a consequence of the recurrence relation (3) above.

In the 1303 AD treatise Precious Mirror of the Four Elements, Zhu Shijie mentioned the triangle as an ancient method for evaluating binomial coefficients indicating that the method was known to Chinese mathematicians five centuries before Pascal.

Combinatorics and statistics

Binomial coefficients are of importance in combinatorics, because they provide ready formulas for certain frequent counting problems:

- Every set with n elements has

different subsets having k elements each (these are called k-combinations).

different subsets having k elements each (these are called k-combinations). - The number of strings of length n containing k ones and n − k zeros is

- There are

strings consisting of k ones and n zeros such that no two ones are adjacent.

strings consisting of k ones and n zeros such that no two ones are adjacent. - The number of sequences consisting of n natural numbers whose sum equals k is

; this is also the number of ways to choose k elements from a set of n if repetitions are allowed.

; this is also the number of ways to choose k elements from a set of n if repetitions are allowed. - The Catalan numbers have an easy formula involving binomial coefficients; they can be used to count various structures, such as trees and parenthesized expressions.

The binomial coefficients also occur in the formula for the binomial distribution in statistics and in the formula for a Bézier curve.

Formulas involving binomial coefficients

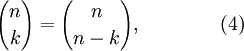

One has that

This follows immediately from the definition or can be seen from expansion (2) by using (x + y)n = (y + x)n, and is reflected in the numerical "symmetry" of Pascal's triangle.

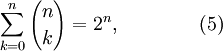

Another formula is

it is obtained from expansion (2) using x = y = 1. This is equivalent to saying that the elements in one row of Pascal's triangle always add up to two raised to an integer power. A combinatorial proof of this fact is given by counting subsets of size 0, size 1, size 2, and so on up to size n of a set S of n elements. Since we count the number of subsets of size i for 0 ≤ i ≤ n, this sum must be equal to the number of subsets of S, which is known to be 2n.

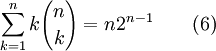

The formula

follows from expansion (2), after differentiating with respect to either x or y and then substituting x = y = 1.

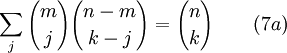

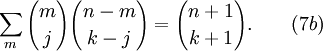

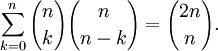

Vandermonde's identity

is found by expanding (1+x)m (1+x)n-m = (1+x)n with (2). As C(n, k) is zero if k > n, the sum is finite for integer n and m. Equation (7a) generalizes equation (3). It holds for arbitrary, complex-valued  and

and  , the Chu-Vandermonde identity.

, the Chu-Vandermonde identity.

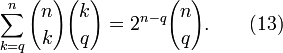

A related formula is

While equation (7a) is true for all values of m, equation (7b) is true for all values of j.

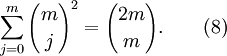

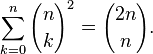

From expansion (7a) using n=2m, k = m, and (4), one finds

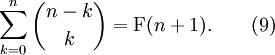

Denote by F(n + 1) the Fibonacci numbers. We obtain a formula about the diagonals of Pascal's triangle

This can be proved by induction using (3).

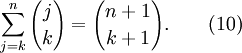

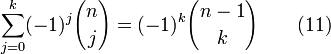

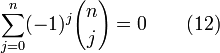

Also using (3) and induction, one can show that

Again by (3) and induction, one can show that for k = 0, ... , n - 1

as well as

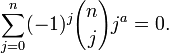

which is itself a special case of the result that for any integer a = 1, ..., n - 1,

which can be shown by differentiating (2) a times and setting x=-1 and y=1.

Combinatorial identities involving binomial coefficients

We present some identities that have combinatorial proofs. We have, for example,

for  The combinatorial proof goes as follows: the left side counts the number of ways of selecting a subset of

The combinatorial proof goes as follows: the left side counts the number of ways of selecting a subset of ![[n]](../../images/197/19706.png) of at least q elements, and marking q elements among those selected. The right side counts the same parameter, because there are

of at least q elements, and marking q elements among those selected. The right side counts the same parameter, because there are  ways of choosing a set of q marks and they occur in all subsets that additionally contain some subset of the remaining elements, of which there are

ways of choosing a set of q marks and they occur in all subsets that additionally contain some subset of the remaining elements, of which there are  This reduces to (6) when

This reduces to (6) when

The identity (8) also has a combinatorial proof. The identity reads

Suppose you have  empty squares arranged in a row and you want to mark (select) n of them. There are

empty squares arranged in a row and you want to mark (select) n of them. There are  ways to do this. On the other hand, you may select your n squares by selecting k squares from among the first n and

ways to do this. On the other hand, you may select your n squares by selecting k squares from among the first n and  squares from the remaining n squares. This gives

squares from the remaining n squares. This gives

Now apply (4) to get the result.

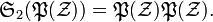

Generating functions

If we didn't know about binomial coefficients we could derive them using the labelled case of the Fundamental Theorem of Combinatorial Enumeration. This is done by defining  to be the number of ways of partitioning

to be the number of ways of partitioning ![[n]](../../images/197/19706.png) into two subsets, the first of which has size k. These partitions form a combinatorial class with the specification

into two subsets, the first of which has size k. These partitions form a combinatorial class with the specification

Hence the exponential generating function B of the sum function of the binomial coefficients is given by

This immediately yields

as expected. We mark the first subset with  in order to obtain the binomial coefficients themselves, giving

in order to obtain the binomial coefficients themselves, giving

This yields the bivariate generating function

Extracting coefficients, we find that

or

again as expected. This derivation is included here because it closely parallels that of the Stirling numbers of the first and second kind, and hence lends support to the binomial-style notation that is used for these numbers.

Divisors of binomial coefficients

The prime divisors of C(n, k) can be interpreted as follows: if p is a prime number and pr is the highest power of p which divides C(n, k), then r is equal to the number of natural numbers j such that the fractional part of k/pj is bigger than the fractional part of n/pj. In particular, C(n, k) is always divisible by n/gcd(n,k).

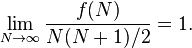

A somewhat surprising result by David Singmaster (1974) is that any integer divides almost all binomial coefficients. More precisely, fix an integer d and let f(N) denote the number of binomial coefficients C(n, k) with n < N such that d divides C(n, k). Then

Since the number of binomial coefficients C(n, k) with n < N is N(N+1) / 2, this implies that the density of binomial coefficients divisible by d goes to 1.

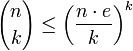

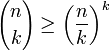

Bounds for binomial coefficients

The following bounds for C(n, k) hold:

Generalizations

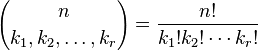

Generalization to multinomials

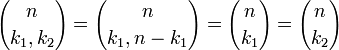

Binomial coefficients can be generalized to multinomial coefficients. They are defined to be the number:

where

While the binomial coefficients represent the coefficients of (x+y)n, the multinomial coefficients represent the coefficients of the polynomial

- (x1 + x2 + ... + xr)n.

See multinomial theorem. The case k = 2 gives binomial coefficients:

The combinatorial interpretation of multinomial coefficients is distribution of n distinguishable elements over r (distinguishable) containers, each containing exactly ki elements, where i is the index of the container.

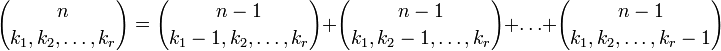

Multinomial coefficients have many properties similar to these of binomial coefficients, for example the recurrence relation:

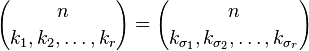

and symmetry:

where  is a permutation of (1,2,...,r).

is a permutation of (1,2,...,r).

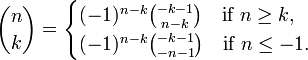

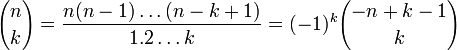

Generalization to negative integers

If  , then

, then  extends to all

extends to all  .

.

The binomial coefficient extends to  via

via

Notice in particular, that

This gives rise to the Pascal Hexagon or Pascal Windmill.

- Hilton, Holton and Pedersen (1997). Mathematical Reflections. Springer. ISBN 0-387-94770-1.

Generalization to real and complex argument

The binomial coefficient  can be defined for any complex number z and any natural number k as follows:

can be defined for any complex number z and any natural number k as follows:

This generalization is known as the generalized binomial coefficient and is used in the formulation of the binomial theorem and satisfies properties (3) and (7).

For fixed k, the expression  is a polynomial in z of degree k with rational coefficients.

is a polynomial in z of degree k with rational coefficients.

f(z) is the unique polynomial of degree k satisfying

- f(0) = f(1) = ... = f(k − 1) = 0 and f(k) = 1.

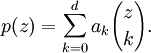

Any polynomial p(z) of degree d can be written in the form

This is important in the theory of difference equations and finite differences, and can be seen as a discrete analog of Taylor's theorem. It is closely related to Newton's polynomial. Alternating sums of this form may be expressed as the Nörlund-Rice integral.

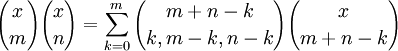

In particular, one can express the product of binomial coefficients as such a linear combination:

where the connection coefficients are multinomial coefficients. In terms of labelled combinatorial objects, the connection coefficients represent the number of ways to assign m+n-k labels to a pair of labelled combinatorial objects of weight m and n respectively, that have had their first k labels identified, or glued together, in order to get a new labelled combinatorial object of weight m+n-k. (That is, to separate the labels into 3 portions to be applied to the glued part, the unglued part of the first object, and the unglued part of the second object.) In this regard, binomial coefficients are to exponential generating series what falling factorials are to ordinary generating series.

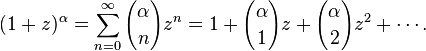

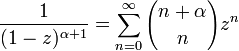

Newton's binomial series

Newton's binomial series, named after Sir Isaac Newton, is one of the simplest Newton series:

The identity can be obtained by showing that both sides satisfy the differential equation (1+z) f'(z) = α f(z).

The radius of convergence of this series is 1. An alternative expression is

where the identity

is applied.

The formula for the binomial series was etched onto Newton's gravestone in Westminster Abbey in 1727.

Generalization to q-series

The binomial coefficient has a q-analog generalization known as the Gaussian binomial.

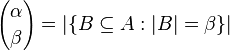

Generalization to infinite cardinals

The definition of the binomial coefficient can be generalized to infinite cardinals by defining:

where A is some set with cardinality  . One can show that the generalized binomial coefficient is well-defined, in the sense that no matter what set we choose to represent the cardinal number

. One can show that the generalized binomial coefficient is well-defined, in the sense that no matter what set we choose to represent the cardinal number  ,

,  will remain the same. For finite cardinals, this definition coincides with the standard definition of the binomial coefficient.

will remain the same. For finite cardinals, this definition coincides with the standard definition of the binomial coefficient.

Assuming the Axiom of Choice, one can show that  for any infinite cardinal

for any infinite cardinal  .

.

Binomial coefficient in programming languages

The notation  is convenient in handwriting but inconvenient for typewriters and computer terminals. Many programming languages do not offer a standard subroutine for computing the binomial coefficient, but for example the J programming language uses the exclamation mark: k ! n .

is convenient in handwriting but inconvenient for typewriters and computer terminals. Many programming languages do not offer a standard subroutine for computing the binomial coefficient, but for example the J programming language uses the exclamation mark: k ! n .

Naive implementations, such as the following snippet in C:

int choose(int n, int k) {

return factorial(n) / (factorial(k) * factorial(n - k));

}

are prone to overflow errors, severely restricting the range of input values. A direct implementation of the first definition works well:

unsigned long long choose(unsigned n, unsigned k) {

if (k > n)

return 0;

if (k > n/2)

k = n-k; // faster

long double accum = 1;

for (unsigned i = 0; i++ < k;)

accum = accum * (n-k+i) / i;

return accum + 0.5; // avoid rounding error

}

Using Pascal's rule  , the algorithm for the binomial coefficient may be written in recursive form:

, the algorithm for the binomial coefficient may be written in recursive form:

function choose(n: integer, k:integer): integer

if k = 0 or k = n then

choose = 1

else

choose = choose(n-1, k-1) + choose(n-1, k)

end if

end function

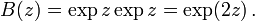

![\sum_{k=0}^{n} {n \choose k} = n! [z^n] \exp (2z) = 2^n,](../../images/197/19718.png)

![{n \choose k} = n! [u^k] [z^n] \exp uz \exp z =

n! [z^n] \frac{z^k}{k!} \exp z](../../images/197/19722.png)

![\frac{n!}{k!} [z^{n-k}] \exp z =

\frac{n!}{k! \, (n-k)!},](../../images/197/19723.png)