New York City College of Technology: A.E. Dreyfuss' "Supporting Students to Succeed: Critical Thinking"

Asking students to “think critically” depends on moving away from testing their recall skills, to having them explain their understanding of a concept or example, to applying the knowledge to a problem. These three skills are “lower-order thinking” skills. Critical thinking asks learners to use “higher-order thinking” skills to analyze a document, a situation, or equipment, examine alternatives and evaluate the proposed final draft, action, or test, and consider the results, which may lead to creation of new knowledge.

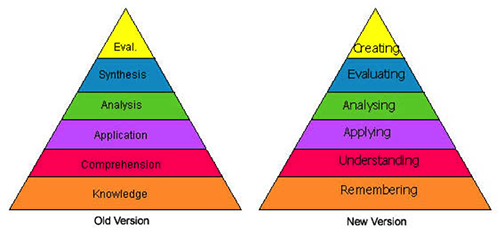

The work of Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in naming stages of cognition (as one part of the committee’s work) is commonly called “Bloom’s Taxonomy” (1956). The six stages move from “knowing” something, to “understanding” followed by being able to apply the knowledge. These first three stages are the lower-order thinking skills. Higher-order thinking skills include “analyzing,” “synthesizing” and “evaluating” the result. Learners benefit by moving from the first three stages toward mastery of higher-order thinking skills in becoming novice-experts.

Bloom’s Taxonomy was revised by a second committee in 2001, led by a student of Bloom’s, Lorin Anderson (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). The words used for each stage changed from nouns to verbs, and both taxonomies are presented in Figure 1.

Comparison of Blooms Taxonomy

Figure 1. Comparison of Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) and revised version (2001). Source: http://epltt.coe.uga.edu

Moving to the fourth through sixth stage demands more sophisticated skills. Improvement is cyclical, that is, the process repeats itself, with ever more challenging work.

# 27. Use Bloom’s Taxonomy

Strategy: The instructor builds lessons on concepts based on the six stages of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognition, revised (2001).

Time: In class time to be allotted

Materials: 1) Exercise and 2) Handout with definitions of each stage of Bloom’s Taxonomy[LINK to version in appendices], (*Definitions below by Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001)

- Remembering: Retrieving, recognizing, and recalling relevant knowledge from long-term memory.

- Understanding: Constructing meaning from oral, written, and graphic messages through interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, and explaining.

- Applying: Carrying out or using a procedure through executing, or implementing.

- Analyzing: Breaking material into constituent parts, determining how the parts relate to one another and to an overall structure or purpose through differentiating, organizing, and attributing.

- Evaluating: Making judgments based on criteria and standards through checking and critiquing.

- Creating: Putting elements together to form a coherent or functional whole; reorganizing elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing.

Process:

Instructor designs an exercise that provides varying levels of complexity. Instructor explains the six stages, providing examples and definitions, which are also in a handout. For example, reading material can be analyzed:

✓ Students in groups decide what text fits with each stage;

✓ Once marked, the instances of text categorized by stage can be tabulated

✓ Compare the amount of text devoted to Lower-Order Thinking skills as opposed to Higher-Order Thinking skills

✓ Discuss why text has been assigned to stages and how thinking becomes more sophisticated at higher stages.

Developing the skills of higher-order thinking is aided by the instructor asking questions that cannot be answered with a yes or no response. As noted by Jacobs (2011), discussion in class can be started with simple questions:

- What is this?

- When did it happen?

- Who did it?

- Who else was involved?

- Where did it happen?

Continue with:

- How is this done?

- How is it related to ___________?

- Why did this happen?

- What are some consequences of this idea, innovation, discovery…?

- What would have happened if this piece of information had been omitted?

- What will happen next? What comes next?

Students master deep learning when they generate their own questions. Making students aware of the questions you have posed provides a base for them to become questioners. Before a topic is introduced, have students write questions based on what they know already, and what they think will come next. They can also be encouraged to write questions for each of the Bloom’s levels.

Sternberg (2003) suggests that to become a “expert student” demands more than the “deliberate practice” espoused by Ericsson et al. (1993) for performance-based expertise (e.g., music, sports). He posits that three additional domains are necessary: “a blend of creative (generate ideas), analytical (evaluate the ideas), and practical thinking (making the ideas work and convince others of their worth)” (Sternberg, 2003, p. 6). These are higher-order thinking skills that meld Bloom’s Taxonomy with skill-building that ties in to workplace and scholarly performance.

“Fair mindedness”

Getting away from “favorable” (agrees with us) and “unfavorable” (disagrees with us) demands a “consciousness of the need to treat all viewpoints alike, without reference to one’s own feelings or selfish interests” (Hansen, 2011). To accomplish this, Hansen (2011) lays out seven intellectual habits of critical thinkers to develop “fair-mindedness.”

- Intellectual humility: Be aware of one’s biases, prejudices, limitations of one’s viewpoint, and the extent of one’s ignorance. If coming from a U.S. or Western European culture which emphasizes competition, individualism, materialism, democratic forms of government, nuclear family arrangements, work ethic, become a student of other types of cultures, which may emphasize opposite views of collaboration, cooperation, shared resources, extended families. These opposing views will impact instructors’ and students’ views of concepts in the social sciences, arts and humanities.

- Intellectual courage: Be aware of the need to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs, or viewpoints toward which one has strong negative emotions and to which one has not given a serious hearing. It takes courage to openly investigate any potentially rational roots for controversial behaviors and beliefs.

- Intellectual empathy: Be aware of the need to put oneself in the place of others to genuinely understand them. In the social sciences, for example, “objectivity” with no emotional involvement is changing to examining the research subjects’ perspective.

- Intellectual integrity: Be aware of the need to be true to one’s own thinking and to hold oneself to the same standards one expects others to meet. This means honestly admitting discrepancies and inconsistencies in one’s own thoughts and actions.

- Intellectual perseverance: Be aware of the need to work one’s way through intellectual complexities despite the frustration inherent in the task. Helping students to realize that difficult questions may not yet have answers, or answers are ambiguous, is a critical task of teaching.

- Confidence in reason: Giving the freest play to reason by encouraging people to come to their own conclusions; faith that with proper encouragement and cultivation people can learn to think for themselves. Instructors can help students to recognize where they have made conceptual errors so they can learn from their mistakes.

- Intellectual autonomy: having rational self-authorship of one’s beliefs, values, and way of thinking; not being dependent on others for the direction and control of one’s thinking. Instructors can support students by making them accountable for their own learning.