|

Potato

Scientific name:

Solanum tuberosum

Order/Family:

Solanales: Solanaceae

Local names:

Kiazi, Egiasi, Mbatata, Potato, Enkwashei (Kenya) / Batata Reno (Mozambique)

Pests and Diseases:

Aphids

Bacterial soft rot

Bacterial wilt

Broomrape

Cutworms

Dodder

Early blight

Epilachna beetles

Late blight

Millipedes

Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid

Potato tuber moth

Root-knot nematodes

Scab

Storage pests

Viral diseases

Weeds

|

Aphids (Myzus persicae, Macrosiphum euphorbiae, Aulacorthum solani, Aphis gossypii)

Many aphid species attack potatoes. The most important are the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) the potato aphids (Macrosiphum euphorbiae, Aulacorthum solani) and the cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii).

Aphids are mainly found on young shoots on the underside of leaves. Feeding by aphids causes irregular curling of young potato leaflets and hinders growth of the leaflet. Potato aphids can also attack potato sprouts in stores.

Direct damage caused by aphids sucking sap from the plant is usually of little importance. Most damage is caused by honeydew production on foliage and virus transmission.

Aphids are important pests as vectors of potato viruses such as the Potato Leaf Roll Virus, a serious disease affecting potatoes. Seed potatoes are particularly susceptible to this virus and even low aphid populations can be very damaging.

- Conserve natural enemies. They are important in natural control of aphids. (Link to natural enemies datasheet).

- Control aphids in potato planted for seed production.

- Site seed production areas in locations with low temperature, abundant rainfall and high wind velocity. Aphid populations are generally low under these conditions.

- Within a potato growing area, locate seed potato fields upwind from commercial potato fields and alternative host crops to reduce dissemination of viruses through aphids carrying viruses.

- Keep seed production areas separated from commercial potato production.

- Check the field regularly. Monitoring of aphid build-up is important.

- Protect young plants from aphid attack. Virus spread early in the season is more serious than later on, as young plants are generally more susceptible. Moreover, plants that are infected early become more efficient sources for further virus spread than plants infected later in the season.

- Harvest seed potatoes no later than 8 to 10 days after a critical aphid build-up or increased virus infection rates are noted. This may help to avoid infection since the virus requires time to infect the tubers after a virus-carrying aphid has fed on potato foliage.

- Remove yellow flowering weeds and any other host plants within and around the field. Aphids are attracted to yellow colour.

- Protect potato tubers during storage by preventing access of aphids. Potato aphids readily colonise tuber sprouts. Seed potatoes are very susceptible to infection at this stage.

- Neem products are useful for reducing aphid populations on potatoes. In Sudan, 2 applications of seed extracts at a rate of 1kg seed kernels/40l water at a 14 days interval reduced aphid (A. gossypii) population to 60% compared to the control (Zebitz, 1995).

- Extracts of the weed Artemisia vulgaris have also shown toxicity to potato aphids (Metspalu and Hiiesar, 1994).

© Magnus Gammelgaard

Bacterial soft rot (Erwinia carotovora pv. carotovora , E.c. pv. atroseptica)

The bacteria enters through wounds and cause extensive rotting of potatoes due to degradation of tuber cell walls, often reducing tubers to a smelly pulp. They may also be carried over on tubers, and shoots (stems) emerging from infected tubers. These are blackened and commonly referred as blackleg, and the affected stems subsequently die.

- Use resistant varieties where available. This constitutes the best management strategy.

- Use healthy seed tubers and avoid injury to the tubers.

- Avoid excess watering.

- Store and transport tubers in dry, well ventilated conditions.

- Practise field hygiene.

© Oregon State University

Bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum)

Bacterial wilt can be very destructive at the lower altitude, warmer extreme of the potato's range in Kenya. This disease causes rapid wilting and death of the entire plant without any yellowing or spotting of leaves. All branches wilt at about the same time. The pathogen is transmitted through tuber seed into the soil. Also infested soil can be important source of disease inoculum (infection).

- Use clean certified disease-free seed.

- Plant resistant varieties where available.

- Remove wilted plants to reduce spread of the disease from plant to plant.

- Bio-fumigation (incorporating especially mustard or radish plants in large amounts into the soil immediately before planting potatoes) helps in reducing and the long-term elimination of bacterial wilt from the soil. This practice is reported to reduce incidence of bacterial wilt by 50 to 70% in the Philippines (ACIAR 2005/6). For more information on biofumigation click here

- Do not grow crops belonging to the same family as potatoes (e.g. tomatoes, peppers or eggplant) in succession in the same land. Rotation is not effective against bacterial wilt because the pathogen can survive for several years in the soil and also can infect a wide range of crops and weeds. However, the disease incidence can be reduced if crop rotation with non-susceptible crops (e.g. cereals) is combined with the other above-mentioned control components.

© Courtesy of EcoPort, www.ecoport.org

Bacterial …

Bacterial …

Cutworms (Agrotis spp)

Cutworms are caterpillars of some moths. The caterpillars live in the soil and eat into tubers boring a wide shallow hole. They are also serious pests of newly sprouted potato plants, and can leave empty patches in a potato field.

- Protect plants by wrapping them with collars. A simple collar can be made from cardboard tubes from paper towels or toilet paper (cut to size). This practice is time consuming, but it is effective and practicable in small fields.

- If necessary spray neem extracts. Neem leaf extracts and neem seed extracts (1 kg/40 l water) have been effective against cutworms attacking potatoes reducing damage significantly in Sudan.

© A.M. Varela, icipe

Early blight (Alternaria solani)

Leaf spots of early blight are circular, up to 12 mm in diameter, brown, and often show a circular pattern.

On the potato tuber early blight results in surface lesions that appear a little darker than adjacent healthy skin. Lesions are usually slightly sunken, circular or irregular, brown and vary in size up to 1-2 cm in diameter. There is usually a well defined and sometimes slightly raised margin between healthy and diseased tissue. Internally, the tissue shows a brown to black corky, dry rot, usually not more than 6 mm. Deep cracks may form in older lesions.

Early blight thrives best under warm wet conditions.

- Use certified disease-free seeds

- Practise rotation with non-solanaceaous crops.

- Practise good field hygiene. Remove infected leaves during the growing season and discard all badly infected potato plant debris at the end of each season.

- Avoid overhead irrigation and lay down a thick organic mulch to prevent soil splashing onto lower leaves.

© Chad Behrendt. Reproduced from University of Minnesota Extension.

Epilachna beetles (Epilachna spp.)

Several species of Epilachna beetles feed on the leaf tissue in between the veins leaving a network of veins intact. The adult beetles are oval, about 6 mm in length and reddish brown to brownish yellow in colour with black spots on their backs. They look very similar to the beneficial ladybird beetles (predators), but the body of this pest ladybird beetle is covered with short, light coloured hairs, which give them a non-glossy or matt appearance.

They lay eggs in clusters (20 to 50 eggs), usually on the underside of the leaves and placed vertically. The larvae (grubs) are pale yellow and easily recognisable by the strong branched spines covering their body. Generally, these beetles are minor pests of potatoes, but occasionally the infestation is so severe that control measures are needed.

- Handpick and destroy adults and larvae of Epilachna beetles. This is feasible in small plots.

- Spray neem extracts. Simple neem-based pesticides have been reported to control Epilachna beetles on several crops. Thus, sprays with an aqueous neem seed extract (10g/l) at 10 days intervals showed repellent effect on these beetles in India. In Togo, feeding by Epilachna beetles in squash and cucumber could be reduced significantly by weekly applications of aqueous neem kernel extracts at concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 g/l and neem oil applied with an ultra-low-volume (ULV) sprayer at 10 and 20 l/ha (Ostermann and Dreyer, 1995).

© A. M. Varela, icipe

Late blight (Phytophthora infestans)

This disease is favoured by cool, cloudy, wet conditions. Symptoms of late blight are irregular, greenish-black, water soaked patches, which appear on the leaves. The spots soon turn brown and many of the affected leaves wither, yet frequently remain attached to the stem.

- Plant resistant varieties where available. In Kenya, varieties "Tigoni", "Kenya Baraka", "Roslin Eburu", "Annet" and "Asante" are claimed to have some resistance to late blight.

- Practise rotation with non-solanaceaous crops (do not rotate with tomatoes and eggplants).

- Practise good field hygiene. Pull up and discard infected plants.

- Select only, certified, disease-free seed potatoes and never plant table-stock potatoes

- Keep foliage dry and avoid overhead irrigation.

- Plant potatoes in sunny, well-drained locations.

- KARI has also conducted studies to evaluate lower cost measures used by farmers to control late blight, including the application of a mixture made of stinging nettle (possibly Urtica massaica, though not indicated) and Omo (presumably the commercial brand of laundry detergent). Although this treatment was not as effective as a commercial fungicide, Ridomil, blight scores were nevertheless lower and yields higher than observed for the control. On a benefit to cost basis, the stinging nettle treatment was impressive, at over two to one (KARI 2000). This treatment is apparently not a common practice in Kenya, at least not yet, but an example of using stinging nettle (Urticaria dioica) as a treatment against late blight in Sweden is reported in Ecology and Society.

© William E. Fry. Reproduced from the Crop Protection Compendium, 2004 Edition. © CAB International, Wallingford.

Late bligh…

Late bligh…

Millipedes or thousand-legged worms

Millipedes are not insects, but are related to them. They have many legs (30 to 400) with a hard-shelled, round segmented body. They are brown to blackish brown in colour. They move slowly and curl up when disturbed. Millipedes lay eggs singly or in clusters of 20 to 100 in the soil. They live in moist soil and congregate around the plants in soil that is rich in organic content. They dry out easily and die. Thus, they seek wet places, such as compost piles, leaves and other plant debris, to hide under during the day. They tunnel into potato tubers.

- Clear hiding places. Remove volunteer plants, crop residues, decaying vegetation, dead leaves, grass, compost piles, excess mulch or other similar debris. Litter under trees, abandoned termite hills, and neglected home nurseries can also harbour large populations of millipedes.

- Avoid wet areas

- Trap millipedes. They like hiding during daytime. They can be attracted by placing flat objects (such as pieces of plywood) on the ground where they hide under and can be collected subsequently.

© A. M. Varela, icipe

Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (PSTVd)

It is particularly destructive for seed production. Potato plants severely infected are upright, stunted and much thinner than normal plants. Leaves of infected plants are smaller and may be grey or distorted. The affected stems are often more branched and branches are at very sharp angles to the stem. Symptoms are more obvious on tubers. Affected tubers are small, narrow and spindle shaped (oblong).

In some varieties tubers develop knobs and swellings. In other varieties eyes on tubers are numerous, shallow and prominent, and affected tubers are often cracked. This viroid is easily mechanically transmitted. An infection can be introduced by sowing infected seed tubers, by insects such as aphids, grasshoppers and flea beetles, and through pollen. Tomato and capsicum are additional hosts for PSTVd.

- Plant certified disease-free seed tubers.

- Plant whole seed tubers instead of cut pieces.

- Remove infected plants from the field.

Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.)

Potatoes are very susceptible to root-knot nematodes. Root-knot nematodes prefer warm temperatures and are likely to become established in potato crops grown in relatively warm areas. Generally, they are not a major problem in cool climate potato production areas, but can become a problem when potatoes are grown intensively or rotated with other susceptible crops. Infested potato plants may show varying degrees of stunting, yellowing of leaves and a tendency to wilt under moisture stress. Roots have swellings or galls. Affected tubers have blisters or swellings.

On potato tubers, galls may or may not be produced on the tuber surface, depending on cultivars. When galls are produced, they appear as small, raised lumps above giving the skin a rough appearance. Galls may be grouped in a single area or scattered near the tuber eyes. Infestations are difficult to detect in freshly harvested potato tubers.

Symptoms may develop when tubers are stored, particularly when taken to warmer climates where nematode numbers can rapidly increase. Symptoms are most severe when crops are grown on sandy soils and warm climates above 25°C. Nematode attack reduces the quality, size and number of tubers.

Root-knot nematode infested potatoes can become more susceptible to bacterial wilt, and symptoms are more severe when plants are also infected with fungal pathogens such as Verticillium and Rhizoctonia.

Root-knot nematodes are mainly spread in potato tubers and in infested soil. Egg masses may be transported into clean fields via soil adhering to farm machinery. Spread within fields occurs during cultivation and in water, during irrigation or natural drainage.

- Practise proper crop rotation (e.g. potato - brassicas - cereals).

- Use mixed cropping or grow marigolds (Tagetes spp.) or sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea).

- Maintain high levels of organic matter in the soil (manure and compost).

- Bio-fumigation (incorporating fresh plant mass, especially mustard or radish plants, in large amounts into the soil before planting potatoes) helps against root knot nematodes. Decomposing plant parts release compounds, which kill nematodes. Two weeks after incorporating plant material into the soil a new crop can be planted (phytotoxic effects are exhibited if the crop is planted before 2 weeks). For more information on biofumigation click here

© Courtesy EcoPort (http://www.ecoport.org): DAFF Archives, www.insectimages.org

Root-knot …

Root-knot …

Black scurf and Scab

Black scurf (Rhizoctonia solani), powdery scab (Spongospora subterranea) and common scab caused by the bacterium (Streptomyces scabies).

These diseases may cause similar symptoms. Black scurf and scab cause skin blemishes (russeting; rough corky tissue) on tubers.

These lesions may be so numerous as to involve the entire surface of affected tubers. Such lesions spoil the appearance of the tubers and cause waste in peeling and reduction in grade. These pathogens live in the soil and survive in infected tubers. In most cases infection occurs whilst the tubers are still in the ground.

- Practise crop rotation.

- In case of scab use healthy certified seed tubers.

- Disinfect seed tubers from infected field through heat-treatment (10 min in water at 55°C). The same treatment of naturally or artificially contaminated seed tubers gave complete absence of blackleg infection in the field and decreased the amounts of powdery scab (Spongospora subterranea) and black scurf (Rhizoctonia solani) on progeny tubers. For more information on heat treatment click here

- Avoid excessive liming and continuous cropping with potatoes.

- Maintain soil pH at about 4.8 if continuous cropping cannot be avoided.

© Courtesy EcoPort (http://www.ecoport.org): McKenzie E., Landcare Ltd., New Zealand

Viral diseases

Viral diseases of importance include:

Potato Leaf Roll Virus (PLRV)

Potato X Potexvirus (PVX)

Potato Virus Y Potyvirus (PVY)

Under field conditions, there is often a composite infection with the 3 viruses (PLRV; PVX; PVY) and it becomes very difficult to distinguish the three on the basis of symptoms.

These viruses are transmitted by aphids. PVX causes distinct leaf mottling and crinkling. PVY causes dwarfing of plants, with a rough, mosaic appearance to the leaves and affected plants give a poor crop of small tubers. PVY is also tuber-borne. Potatoes infected with PLRV show an upward and inward rolling of leaflet margins and plants are dwarfed. Affected leaflets become thick and dry, and the lower leaves may become completely brown. Infected plants produce tubers smaller in size and numbers. PLRV also infects other solanaceous crops and weeds (e.g. tomato, tobacco, jimson weed).

- Use virus-free seed tubers.

- Plant resistant varieties where available. In Kenya, the following potato varieties are claimed to possess some resistance to viral diseases: "Kenya Baraka", "Roslin Eburu", "Feldelslohn", "Annet" and "Dutch Robjn".

- Uproot infected plants to reduce the incidence of infection and spread of the disease within a field. For maximum effectiveness remove the diseased plant, the 3 plants on each side of the diseased plant in the same row, and the three closest plants in adjacent rows. This is particularly important in seed fields.

- Control of insect vectors may reduce virus spread.

- Do not overlap potato crops.

- Practise good field sanitation.

- Control nightshades and volunteer potatoes because these plants are reservoirs for viruses

Weeds

The major weeds in potato crops are annuals. Weeds can reduce yields through direct competition for light, moisture and nutrients. They may harbour pests and diseases that attack potatoes. Early season competition of weeds is very critical. When properly grown, the crop normally covers the ground and smothers any weed competition. Weeds present at harvest increase mechanical damage to the tubers, and reduce harvesting efficiency by slowing down harvesting operations and leaving tubers in the ground. The most important weed in potatoes worldwide is pigweed or fat hen (Chenopodium album).

- Practise crop rotation. Rotation of 2 or 3 years is an important strategy to control perennial weeds. Weeds tend to thrive with crops of similar growth requirements as their own and may benefit from practices directed to the crop. When diverse crops are used in a rotation, weed germination and growth cycles are disrupted by variation in cultural practices associated with each crop.

- Control weeds early in the season. It is important to stop broadleaved weeds or annual grasses from appearing above the crop and competing strongly for nutrients and moisture when tubers are enlarging.

© Courtesy EcoPort (http://www.ecoport.org): Photography courtesy of Western Weeds CD-ROM. Web version by R. Randall.

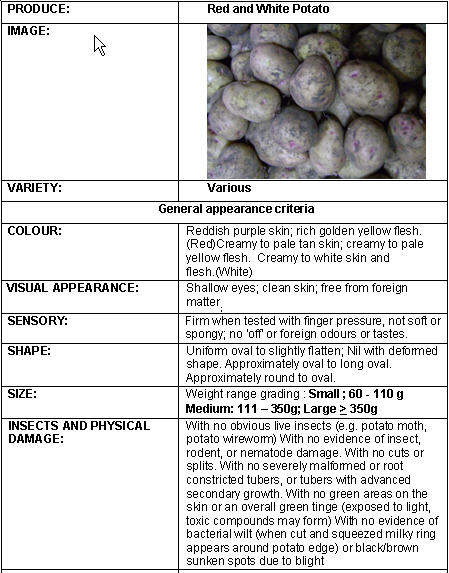

| General Information and Agronomic Aspects | Information on Diseases | |||

| Fresh Quality Specifications for the Market in Kenya | Information Source Links | |||

| Information on Pests and Weeds | Contact Information |

|

| Geographical Distribution of Potato in Africa |

Nutritive Value per 100 g of edible Portion

| Raw or Cooked Potato | Food Energy (Calories / %Daily Value*) |

Carbohydrates (g / %DV) |

Fat (g / %DV) |

Protein (g / %DV) |

Calcium (g / %DV) |

Phosphorus (mg / %DV) |

Iron (mg / %DV) |

Potassium (mg / %DV) |

Vitamin A (I.U) |

Vitamin C (I.U) |

Vitamin B 6 (I.U) |

Vitamin B 12 (I.U) |

Thiamine (mg / %DV) |

Riboflavin (mg / %DV) |

Ash (g / %DV) |

| Potato baked (flesh and skin) | 93.0 / 5% | 21.2 / 7% | 0.1 / 0% | 2.5 / 5% | 15.0 / 1% | 70.0 / 7% | 1.1 / 6% | 535.0 / 15% | 10.0 IU / 0% | 9.6 / 16% | 0.3 / 16% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 4% | 0.0 / 3% | 1.3 |

| Potato cooked in skin (with skin) | 78.0 / 4% | 17.2 / 6% | 0.1 / 0% | 2.9 / 6% | 45.0 / 4% | 54.0 / 5% | 6.1 / 34% | 407 / 12% | 0.0 / 0% | 5.2 / 9% | 0.2 / 12% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.0 / 2% | 2.0 |

| Red Potato baked (flesh and skin) | 89.0 / 4% | 19.6 / 7% | 0.2 / 0% | 2.3 / 5% | 9.0 / 1% | 72.0 / 7% | 0.7 / 4% | 545 / 16% | 10.0 IU / 0% | 12.6 / 21% | 0.2 / 11% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 5% | 0.1 / 3% | 1.3 |

Climatic conditions, soil and water management

Potato requires well-distributed rainfall of 500 to 750 mm in a growing period of 3 to 4.5 months. Most commercial cultivars of potato tuberise (form tubers) best in cool climates with night temperatures below 20°C. Optimum day temperatures are within the range of 20 to 25°C. Short day lengths (12 to 13 hours) lead to early maturity. In the short day length conditions of the tropics and subtropics, maximum yields can usually be obtained in cool highland areas and in cooler seasons. Cultivation is concentrated in highland areas from 1200 to 3000 m above sea level.In regions with a critical dry season, planting early in the rainy season is best. If the rainy season is long and excessive, time of planting is usually towards the end of the rainy season.

Potato is tolerant to a rather wide variety of soils, except heavy, waterlogged clays. Good drainage is of great importance. Impermeable layers in the soil limit rooting depth and the amount of available water, and so greatly reduce yields. Deep soils with good water retention and aeration give best growth and yields. The most suitable soil pH is between 4.8 and 6. At higher pH, tubers are liable to suffer from scab disease.

Recently, the use of true potato seed for propagation has aroused great interest. True seed does not transmit most of the potato diseases, is very light and is easy to transport. Promising methods to grow potatoes from true seed include raising seedlings in a nursery and transplanting them to the field.

Tubers planted to produce potatoes for consumption should generally be planted in rows 75-100 cm apart with a spacing of 30 to 40 cm within the row (25 to 44,000 plants per ha). The closer spacing should be used in fertile soils and good rainfall areas to avoid the production of very large tubers. Seed potatoes are planted at a spacing of 15 to 20 cm within the row (about 80,000 plants per ha).

Potatoes are planted at a depth of 5 to 15 cm (measured from the top of the tuber). Planting depth is greater under warm, dry conditions than under cool, wet conditions. Shallow plantings should be avoided, because the lower nodes of the stem must remain covered to encourage tuberisation (tuber initiation) and to avoid greening of tubers and tuber moth damage. Earthing up or hilling is carried out to control weeds and to avoid greening of the tubers. Potatoes are normally planted by hand in developing countries, but mechanical planters are available.

Plough-under or incorporate available organic manures in the soil before planting to enhance the water-holding capacity and texture of the soil as well as to provide enough nutrients for a healthy crop. A high yielding potato crop under conventional farming removes 95 to 140 kg N (nitrogen)/ha, 35 kg P (phosphorus)/ha, 125 to 170 kg K (potassium)/ha and has relatively high needs for Mg (magnesium) and Mn (manganese). Organic farmers will need to identify organic sources for similar amounts of nutrients. Potatoes respond well to large amounts of compost or well-rotted animal manures.

Fertiliser recommendations based on soil analysis offer the very best chance of getting the right amount of fertiliser without over or under fertilising. Ask for assistance from the local agriculturist office for soil sampling and soil analysis procedures.

Sources of seed potatoes

In Kenya certified healthy seed potatoes are available from KARI Research Station, Ol Joro Orok and Tigoni Research Station (CIP).

| Variety | Yield | Storage | Drought resistance | Late blight | Viruses | Maturity | Eco-zone |

| "Kenya Baraka" | High | Good | Some resistance | Some resistance | Some resistance | Medium | Medium High |

| "Roslin Eburu" | Medium High | Very good | Resistant | Some resistance | Some resistance | Medium | Medium High |

| "Feldelslohn" | High | Fairly good | Some resistance | Very susceptlible | Some resistance | Medium late | High |

| "Annet" | High | Good | Some resistance | Some resistance | Some resistance | Early | High Medium Low |

| "Dutch Robjn" | High | Very good | Some resistance | Susceptible | Some resistance | Medium | High Medium |

| "Roslin Tana" | High | Fair | Some tolerance | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

| "Roslin Gucha" | Medium | Good | Tolerant | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

| "Desiree" | Medium | Fairly good | Some tolerance | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

| "Roslin Ruaka" | High | Good | Some tolerance | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

| "Cardinal" | Medium | Good | Some tolerance | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

| "Pimpernel" | Medium | Good | Some tolerance | - | - | Medium | High |

| "Arka" | High | Good | Tolerant | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

| "Kerr's Pink" | Medium | Good | Tolerant | - | - | Medium | High Medium |

Note:

High eco-zone = 2300 m altitude

Medium = 1500-2300 m altitude

Low = below 1500 m altitude

High yield = 12-15 tons/ha

Medium yield = 8-10 tons/ha

Low yield = 4-6 tons/ha

(Source: Ministry of Agriculture & Rural Development and Japan International Development Agency (2000)).

| Variety Name | Estimated area harvested (%) | Trend in area* | Strengths of variety | Weakness of variety | Main uses of variety |

| "Tigoni" | 30 | Increasing | High yielding, resistant to late blight, big tubers | Sensitive to bacterial wilt | Market |

| "Nyayo" | 25 | Declining | Early maturing, tasty | Sensitive to late blight | Market, home use |

| "Ngure" | 8 | Increasing | High price, early maturing, tasty | Sensitive to late blight | Market and home use |

| "Tana Kimande" | 7 | Increasing | Big tubers, good price | Low yields, late maturing | Market |

| "Asante" | 6 | Increasing | High yielding, resistant to late blight, big tubers | Not good for mashing | Market |

| "Dutch Robijn" | 5 | Increasing | Storage long, crisping | Sensitive to late blight | Market Crisps |

| "Kerr's Pink" | 3 | Declining | High price, early maturing, tasty | Sensitive to late blight | Market, home use |

| "Desiree" | 3 | Constant | Storage long, tasty | Sprout very early | Market |

| "Tigoni Red" | 3 | Increasing | High yielding, resistant to late blight | Sprout very early | Market |

| "Komesha" | 2 | Constant | High yield | Sensitive to bacterial wilt | Market |

| "Meru Mugaruro" | 2 | Increasing | High yield, big tubers | Sensitive to late blight and bacterial wilt | Market |

| "Roslin Tana" | 2 | Declining | Good for chips | Low yields, sensitive to late blight | Market |

| Others | 4 | Increasing | - | - | Home, market |

| Variety name | Optimal production altitude (masl) | Duration to maturity (months) | Tuber yield (t/ha) | Special attributes |

| "Purple Gold" | 1800-3000 | 4.0-4.5 | 20 - 35 |

|

| "Kenya Mpya" | 1400-3000 | 3.0-3.5 | 35-45 |

|

| "Sherekea" | 1800-3000 | 3.5-4.0 | 40 - 50 |

|

Potato responds well to high soil fertility. Manure or compost is needed if the land has been continuously cropped. Well-decomposed animal manure or compost is recommended.

Ridging soon after emergence helps control weeds, prevents greening of developing tubers and prevents spores of late blight fungus from reaching the tubers.

Intercropping

Wide ridges or mounds are required for intercropping. Potatoes can be intercropped with a wide range of annual crops such as sweet potato, maize or even pyrethrum. Potatoes planted in rotation or intercropped with barley, maize, peas, or wheat prevents soil exhaustion. In this case, intercrops are planted at the bottom or at the edge of the furrows and the potatoes on the ridge.

However in order to get full benefit from a potato crop such as high yields, weed suppression and ease of management, without building up high levels of soil-borne diseases: it is recommended to grow potatoes in a separate field and rotate the crop with others. Interplanting with a short season legume such as beans can increase total crop yield and help prevent spread of diseases.

Crop rotation

Avoid planting potatoes in the same field for several consecutive seasons. Proper crop rotation enhances soil fertility, increases soil organic matter, conserves soil moisture and helps maintain soil structure. In addition, it avoids build-up of soil-borne pathogens affecting potato, and reduces the level of soil infestation once the soil has been contaminated. Rotations should not include crops that are common hosts for diseases and pests of potatoes (e.g. tomato, eggplant, pepper). Rice, maize and legumes are recommended for crop rotation practices. Planting brassicas such as broccoli, cabbage and mustard plants before the potato crop helps reducing incidence of bacterial wilt and nematodes. Control volunteer potatoes and weeds in the rotation crop.

The harvesting operation involves destroying the aboveground parts (haulm), lifting and collecting the tubers. A general practice to avoid excess mechanical damage to tubers at harvesting is to cut the tops 10 to 14 days before lifting the potatoes to give them time to develop matured and hardened skins. The haulm is destroyed either by manual or mechanical cutting.

In small-scale farming in the tropics, lifting is done manually using simple implements such as sticks, hoes and spades. Mechanical harvesting is carried out only in large-scale farming areas using various types of potato diggers, for example, ploughs, spinners or elevator diggers. Semi-automatic diggers lift the tubers from the soil for hand-picking or collection. Harvesting should not be done during or immediately after rain.

Before the tubers go into storage, rotten and infected tubers, which may become sources of post-harvest disease infection, should be removed. Potato tubers are usually delivered into stores in bags, baskets or crates. To facilitate handling, containers should not be too large; if they are large they should not be filled completely. Storage of ware potatoes for the market is associated with undesirable quality changes (mainly sprouting, high sugar content, and weight loss due to evaporation and respiration). For short-term storage (1-2 weeks) in the tropics, ware potatoes may be stored at ambient temperatures in the dark, in well-ventilated buildings. Small-scale farmers can keep potatoes in on-farm storage using inexpensive, well-ventilated constructions.

|

| © S. Kahumbu, Kenya |

|

Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) Potatoes are very susceptible to root-knot nematodes. Root-knot nematodes prefer warm temperatures and are likely to become established in potato crops grown in relatively warm areas. Generally, they are not a major problem in cool climate potato production areas, but can become a problem when potatoes are grown intensively or rotated with other susceptible crops. Infested potato plants may show varying degrees of stunting, yellowing of leaves and a tendency to wilt under moisture stress. Roots have swellings or galls. Affected tubers have blisters or swellings. |

Root-knot nematodes on potato

Root-knot nematodes Meloidogyne incognita damage on potato © Courtesy EcoPort (http://www.ecoport.org): DAFF Archives, www.insectimages.org |

|

What to do:

|

|

Bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) Bacterial wilt can be very destructive at the lower altitude, warmer extreme of the potato's range in Kenya. This disease causes rapid wilting and death of the entire plant without any yellowing or spotting of leaves. All branches wilt at about the same time. The pathogen is transmitted through tuber seed into the soil. Also infested soil can be important source of disease inoculum (infection). |

Bacterial wilt

Bacterial wilt of potato tuber © Courtesy of EcoPort, www.ecoport.org |

|

What to do:

|

|

Black scurf and Scab

Black scurf (Rhizoctonia solani), powdery scab (Spongospora subterranea) and common scab caused by the bacterium (Streptomyces scabies). |

Scab

Citrus scab on leaf © Courtesy EcoPort (http://www.ecoport.org): McKenzie E., Landcare Ltd., New Zealand |

|

What to do:

|

- Acland, J.D. (1980). East African Crops. FAO / Longman. ISBN: 0 582 60301 3

- Agricultural Information Resource Centre (2011). Agricultural Information Directory 2011/2012. Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN: 9966 764 08 9

- Ali, M.A (1993). Effects of cultural practices on reducing field infestation of potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella) and greening of tubers in Sudan. Journal of Agricultural Science, 121(2): 187-192; 19 ref.

- Berg, G. (2006). Agriculture notes. Root-knot nematode on potatoes. AG0574. ISSN 1329-8062. State of Victoria, Department of Primary Industries.

- Bohlen, E. (1973). Crop pests in Tanzania and their control. Federal Agency for Economic Cooperation (bfe). Verlag Paul Parey. ISBN: 3-489-64826-9.

- CAB International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 Edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

- CIP Nairobi (2005). Estimates of Currently grown potato cultivars.

- Centipedes and millipedes. Later's Pest Info Bulletin.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2002). Meloidogyne chitwoodi (the Columbia root-knot nematode) and Meloidogyne fallax www.defra.gov.uk

- Godfrey,L. D., Davis, U.C., Haviland, D. R.(2003). UC Pest Management Guidelines. How to Manage Pests. Potato Aphids, green peach aphid (Myzus persicae), potato aphid (Macrosiphum euphorbiae)]. UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines: Potato. UC ANR Publication 3463. Insects. UC Cooperative Extension, Kern Co. (Reviewed 6/03, updated 6/03). Statewide IPM Program, Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California.

- International Year of the potato www.potato2008.org

- Karren, J. B. Millipedes. Fact sheet No. 21. Revised April 2000. extension.usu.edu

- Kfir, R. (2003). Biological control of the potato tuber moth Phthorimaea opercullela in Africa. In: Neuenschwander, P. - Biological Control in IPM Systems in Africa.

- Kroschel, J. (1995). Integrated pest management in potato production in the Republic of Yemen- with special reference to the integrated biological control of the potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella Zeller). Tropical Agriculture 8.GTZ. Margraf Verlag. ISBN: 3-8236-1242-5.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (Kenya) & Japan International Cooperation Agency (2000). Local and Export Vegetables Growing Manual. Reprinted by Agricultural Information Resource Centre, Nairobi, Kenya. 274 pp.

- Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

- Oisat. Organisation for Non-Chemical Pest Management in the Tropics. www.oisat.org

- Ostermann, H. and Dreyer, M. (1995). Neem Products for Pest management. Vegetables and grain legumes. In: The Neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other meliaceous plants sources of unique natural products for integrated pest management, industry and other purposes. Edited by H. Schmutterer in collaboration with K. R. S. Ascher, M. B. Isman, M. Jacobson, C. M. Ketkar, W. Kraus, H. Rembolt, and R.C. Saxena. VCH. pp. 392-403. ISBN: 3-527-30054-6.

- Potatoes. Kenya Overview research.cip.cgiar.org

- Saxena, R. C. (1995). Neem Products for Pest management. Pest of stored products. In: The Neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other meliaceous plants sources of unique natural products for integrated pest management

- Zebitz, C. P. W. (1995). Neem Products for Pest management. Root and Tuber Crops. In "The Neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other meliaceous plants sources of unique natural products for integrated pest management, industry and other purposes". (1995). Edited by H. Schmutterer in collaboration with K. R. S. Ascher, M. B. Isman, M. Jacobson, C. M. Ketkar, W. Kraus, H. Rembolt, and R.C. Saxena. VCH. pp. 403-407. ISBN: 3-527-30054-6.

- Zitter, T.A., Gallenberg, D.J. (2002). Virus and viroid diseases of potato. Department of Plant Pathology, Cornell University. www.vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu

- Corner Shop, Nairobi cls@mitsuminet.com

- Food Network East Africa Ltd info@organic.co.ke Tel. +254 0721 100 001

- Green Dreams admin@organic.co.ke Tel. +254 0721 100 001

- Kalimoni Greens kalimonigreens@gmail,com Tel +254 0722 509 829

- Karen Provision Stores karenstoresltd@yahoo.com Tel. 020885552

- Muthaiga Green Grocers, Nairobi

- Nakumatt Supermarket info@nakumatt.net Tel. 020551809

- Uchumi Supermarket

- Zuchinni Green Grocers , Nairobi Tel. 0204448240

Back

Back