Joel Brand

About this schools Wikipedia selection

SOS Children, an education charity, organised this selection. Sponsoring children helps children in the developing world to learn too.

| Joel Brand | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 25 April 1906 Naszod, Transylvania (now Năsăud, Romania) |

| Died | 13 July 1964 (aged 58) Israel |

| Cause of death | Liver disease |

| Known for | "Blood for goods" proposal |

| Spouse(s) | Hansi Hartmann |

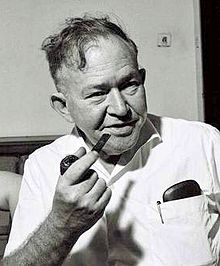

Joel Brand (25 April 1906 – 13 July 1964) was a sailor and odd-job man, originally from Transylvania but raised in Germany, who became known for his efforts during the Holocaust to save the Hungarian-Jewish community from deportation to the concentration camp at Auschwitz. He is remembered in particular for his negotiations with the German Schutzstaffel (SS) officer, Adolf Eichmann, to exchange one million Jews for trucks and other goods, a deal the Nazis proposed and called "Blut gegen Waren" ("blood for goods").

Brand was a member in the 1940s of the Hungarian Aid and Rescue Committee, an organization of Zionists who helped Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe escape to the relative safety of Hungary, before the German invasion of that country on 19 March 1944. Shortly after the invasion, Brand was summoned to a meeting with Eichmann, who had arrived in Budapest to oversee the deportation of the Jewish community. Eichmann asked Brand to help broker a deal between the SS and the United States or Britain, in which the Nazis would release up to one million Jews in exchange for 10,000 trucks for the Eastern front, and large quantities of soap, tea and coffee.

Nothing came of the proposal, described by The Times as one of the most loathsome stories of the war. Historians believe the Germans intended it to serve as a cover for high-ranking Nazi officers, including Heinrich Himmler, to negotiate a peace deal with the Western Allies that would exclude the Soviet Union, and perhaps Adolf Hitler himself. Whatever its purpose, the proposal was thwarted by the Jewish Agency for Israel and a suspicious British government. The British arrested Brand in Turkey, where he had gone to inform them of Eichmann's offer, then leaked the story to the BBC, which broadcast it on 19 July 1944.

The actions of the British government and the Jewish Agency – and the wider issue of why the Allies were unable to save the 435,000 Hungarian Jews deported to Auschwitz between May and July 1944 – have been the subject of bitter debate ever since. Hungarian Holocaust survivors have argued that the failure to act on Eichmann's offer was an unforgivable betrayal. Brand told a court in Jerusalem in 1953: "Rightly or wrongly, for better or for worse, I have cursed Jewry's official leaders ever since. All these things shall haunt me until my dying day. It is much more than a man can bear."

Background

Early life

Brand was born in Naszod, Transylvania, before moving with his family in 1910 to Erfurt in Germany. When he was 19, he went to stay with an uncle in New York, then worked his way across the United States, shovelling snow, washing dishes, working on roads and in an architect's office. Bauer writes that he joined the Communist Party, then worked for the Comintern as a sailor. He travelled to Hawaii, the Philippines, Japan, China, and South America, before returning to Germany in 1930, where he became a party functionary in Thuringia and worked for a telephone company.

Brand was in Germany on 30 January 1933, when Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor. Brand's Communist Party membership led to his arrest four weeks later, after the Reichstag fire on 27 February, when the Nazis began rounding up communists and socialists. When he was released in 1934, he left Germany and settled in Budapest, Hungary, where he worked for the telephone company his father had started, and became a Zionist, joining the Po'alei Zion, a Marxist-Zionist party. He was also a vice-president of the Budapest Palestine Office, and sat on the governing body of the Jewish National Fund.

Aid and Rescue Committee

In 1935 Brand married Hansi Hartmann, another member of the Zionist movement in Budapest, and together they opened a knitwear and glove factory on Rozsa Street. They had met as members of a group of Jews who were living communally, sharing housing and money, as they trained for a move to Palestine, though Brand's plans changed when his mother and three sisters fled to Budapest from Germany, and he had to support them financially. Hansi ran the workshop, while Brand was supposed to sell the goods, but Robert Florence writes that Brand was not happy as a salesman. He was a gregarious man who preferred meeting women, sitting in cafes and playing cards, writes Florence, and could win in a night at poker what it took him to earn in a week of selling gloves.

In July 1941 Hansi's sister and brother-in-law were caught up in the Kamenets Podolskiy deportations, when the Hungarian government deported 18,000 Jews to German-occupied Ukraine, because they were unable to prove that they had Hungarian citizenship. Between 14,000 and 16,000 of them were shot by the SS on 27 and 28 August 1941. Brand paid a Hungarian counter-espionage officer, Joszi Krem, 10,000 pengoes to bring Hansi's relatives back safely. The incident marked the beginning of Brand's involvement in smuggling Jewish refugees from Poland and Slovakia to the relative safety of Hungary.

Brand teamed up with other Zionists engaged in rescue work, including Rudolf Kastner, a lawyer and journalist from Cluj, and Samuel Springmann, a Polish Jew who owned a jewellery store. They were joined in early 1943 by Ottó Komoly, a Budapest engineer and member of the Liberal Zionist Party. Highly respected within the city's Jewish community, Komoly's membership gave the group credibility. He became their chairman, and with that, the Va'adat Ezrah Vehatzalah be-Budapest – the Aid and Rescue Committee (Vaada for short) – was born. The committee consisted of Komoly, Kastner, Joel and Hansi Brand, Samuel Springmann, Sandor Offenbach, Andreas Biss, Dr. Miklos Schweiziger, Moshe Krausz, Eugen Frankl, and Erno Szilagyi from the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair. Brand told the court during the trial of Adolf Eichmann that, between 1941 and March 1944, the group helped 22,000–25,000 Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe reach Hungary.

March–October 1944

Invasion of Hungary (19 March)

The Germans invaded Hungary on Sunday, 19 March 1944, meeting no resistance. Orders were issued that Jews had to wear the Star of David; Jewish bank accounts were closed and their money sequestered; and all Jews had to draw up a detailed inventory of their possessions.

Brand was hidden in a safehouse by Josef Winniger, a courier for German military intelligence, who had been selling Brand information about Jewish refugees. The Aid and Rescue Committee decided to try to establish contact with the Germans, and offered a go-between $20,000 if he could arrange a meeting with one of Eichmann's assistants, SS officer Dieter Wisliceny. Another Zionist rescue worker, Gizi Fleischmann, had had contact with Wisliceny before, in Bratislava, while working for the Women's International Zionist Organization. The committee decided to continue with Wisliceny where Fleischmann had left off.

They offered Wislicency $2 million, at $20,000 a month, if he would ensure no ghettoes or camps would be set up in Hungary, there would be no deportations or mass executions, and that Jews who held certificates allowing them to emigrate to Palestine would be allowed to do so. Wislicency agreed to consider some of the conditions, and said he would accept $200,000 as a down-payment.

First meeting with Eichmann (25 April)

Following the contact with Wislicency, Brand received a message on 25 April that Eichmann himself wanted to see him that day. He was to wait in the Opera Cafḗ, where an SS car would arrive to pick him up; from there he was taken to the Hotel Majestic, where Eichmann had set up his headquarters. Brand testified in 1953 – during the trial in Jerusalem of Malchiel Gruenwald, accused of libeling Rudolf Kastner – "The words which then passed between us have imprinted themselves on my memory till I die." Brand said Eichmann rose to greet him, introduced himself, then said, in a tone that reminded Brand of the "clatter of a machine gun":

I have got you here so that we can talk business. I have already made investigations about you and your people and I have verified your ability to make a deal. Now then, I am prepared to sell you one million Jews. ... Goods for blood – blood for goods. You can take them from any country you like, wherever you can find them – Hungary, Poland, the Ostmark, from Theresienstadt, from Auschwitz, wherever you like.

Brand asked Eichmann how the committee was supposed to obtain the goods, and said Eichmann suggested he go abroad and negotiate directly with the Allies. Eichmann told him they wanted any kind of cargo, but particularly trucks: 10,000 trucks for a million Jews. He also asked for one thousand tons of tea and coffee, and soap. According to Bauer, Hermann Krumey, an assistant of Eichmann's, asked for machine tools, leather and other goods, but the proposal soon settled into 10,000 trucks and various consumer items. Figures that were mentioned, according to later testimony from Rudolf Kastner, were 200 tons of tea, 200 tons of coffee, 2,000,000 cases of soap, 10,000 trucks for the Waffen-SS to be used on the eastern front, and unspecified quantities of tungsten and other war materials.

Eichmann said he was willing to offer one thousand Jews in advance, and a further ten percent on receipt of the first payment. Brand was asked where he wanted to go to make the offer to the Allies and chose Istanbul. When he asked what assurance Eichmann could offer that the Jews would be released, Eichmann responded that, when Brand returned from Istanbul with confirmation that the Allies had accepted, he would "dissolve" Auschwitz and release 10 percent of the one million Jews to the border, in exchange for the first shipment of 1,000 trucks. The deal would thereafter proceed step by step in the same way: 1,000 trucks in exchange for every 100,000 Jews. "You are getting away cheap," Eichmann is said to have added.

Brand told the Gruenwald trial that, on leaving the building, he felt like a "stark madman." He testified: "What were we to do with this monster's offer? ... I had gotten to know the Germans and their cruel lies exceedingly well. But the thought of 100,000 Jews 'in advance' tortured my mind and gave me no respite. I had no right to think of anything but this advance payment." He believed that if he could return from Istanbul with a promise, at least the first 100,000 might be saved.

Significance of the meeting

According to Brand, Untersturmbannführer Kurt Becher, an SS officer and emissary of Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, was standing behind Eichmann during the meeting. If this is correct, it means the meeting was of extraordinary importance, according to Bauer. Brand also testified that Gerhard Clages, the chief of Himmler's Security Service in Budapest, and a rival of Eichmann's, was present at a later meeting, again with Becher and Eichmann. Bauer writes that this meant Himmler had involved three of his men of the same rank to negotiate with Brand: Eichmann, whose job it was to kill Jews; Clages, whose task for Himmler was to reach out to forge a positive relationship with the West, because Germany knew it was losing the war; and Becher, who according to Bauer was meant to ensure the SS did not lose any money or goods.

Second meeting with Eichmann (15 May)

Brand met Eichmann once more, on 15 May. Eichmann told him the deportations from Hungary to Auschwitz were about to begin – which they did that day, at a daily rate of between 7,000 and 12,000 Jews from then until 7 July – but said the deportees would not be killed while negotiations were ongoing.

Gerhard Clages handed Brand $50,000 and 270,000 Swiss francs. Brand told U.S. emissary Ira Hirschmann during an interview on 22 June 1944 that Eichmann had offered to blow up Auschwitz – "dann sprenge ich Auschwitz in die Luft" – and free the first "ten, twenty, fifty thousand Jews" as soon as he heard from Istanbul that an agreement had been reached in principle.

Eichmann told Brand he was free to travel but should return to Budapest soon. According to Bauer, Brand was not consistent in his testimony regarding how long Eichmann had given him, but said at various points that it was one or two weeks, two or three weeks, or that he could "take [his] time." A report prepared by Kastner and entered as evidence during Eichmann's trial states that Eichmann expected Brand to return within two weeks. Hansi Brand testified during Eichmann's trial that she and Brand met Eichmann the day before Brand left for Istanbul, and she was given to understand that she and her children would be held in Budapest until her husband returned.

"Blood for goods" mission

Brand leaves for Istanbul (17 May)

The day after his last meeting with Eichmann, Brand secured a letter of recommendation from the Zentralrat der Ungarischen Juden (the main Hungarian Judenrat) and was told he had a travelling companion, Bandi Grosz (real name Andor Gross, also known as Andrea Gyorgy), a Hungarian-Jewish convert to Catholicism, alleged by various sources to have been a spy for the Germans, Hungarians, British, and Americans. Grosz was travelling undercover as the director of a Hungarian transport company engaged in talks with the Turkish state transport corporation. The men left Budapest on 17 May 1944 and were driven by the SS to Vienna, where they stayed the night in a hotel reserved for SS personnel.

Historians now view Brand's trip as a cover for Grosz's mission. Grosz, who was low level enough to provide plausible deniability for the Germans in case anything went wrong, later testified that he had been told by Clages, on behalf of Heinrich Himmler, to arrange a meeting in a neutral country between two or three senior German security officers and American officers of equal rank – or British officers as a last resort – to negotiate a separate peace between the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD) (part of the SS) and the Western Allies, a peace deal that would exclude the Soviet Union. Grosz later explained: "The Nazis know that they have lost the war. They know that peace cannot be reached with Hitler. Himmler wants to use all possible contacts to get down to negotiations with the Allies."

Meeting with the Jewish Agency (19 May)

In Vienna, Brand was given a German passport in the name of Eugen Band. Brand cabled ahead to the Jewish Agency in Istanbul to say he was about to arrive, then flew first to Sofia, then to Istanbul, by German diplomatic plane, arriving on 19 May. Paul Lawrence Rose writes that Brand had no idea at this point that the deportations to Auschwitz had already begun. He had been told by the Jewish Agency by return cable that "Chaim" would be in Istanbul to meet him. Convinced of the importance of his mission, he believed this referred to Chaim Weizmann, then president of the World Zionist Organization, who later became the first president of Israel. But in fact the man who intended to meet him was Chaim Barlas, head of the Istanbul group of Zionist emissaries.

Brand was further confused when, arriving in Istanbul, he found that, not only was no one waiting to meet him at the airport and no entry visa had been arranged, but that he was threatened with arrest and deportation, which he later took as the first sign of betrayal by the Jewish Agency. Bauer argues that Brand, then and later, never understood the actual powerlessness of the Jewish Agency. The fact that his passport was in the name of Eugen Band, and not Joel Brand, would in itself have been enough to cause the confusion. The visa situation was eventually sorted out by Bandi Grosz, and the men were taken to a hotel, where the Jewish Agency emissaries were waiting.

Raul Hilberg writes that Brand was angry and excited, arguing that he had to telegraph his wife the next day to say that the agreement was secured, but matters were not so simple for the Jewish Agency. They could not be sure that their telegrams to Jerusalem would not be intercepted. No one had the influence to obtain a plane. No one from the War Refugee Board was available. The American Ambassador was in Ankara and no seat on a plane could be found for a trip there.

They told Brand that Moshe Sharett, head of the Jewish Agency's political department, and the Zionist movement's chief ambassador and negotiator with the British in the British Mandate of Palestine (and later the second prime minister of Israel), would be arriving in Istanbul to meet him, which gave Brand hope that the situation was being taken seriously. He passed them an accurate plan of the Auschwitz complex (probably from the Vrba-Wetzler report) and demanded that the gas chambers and railways lines be bombed. According to Hilberg, Brand later said that he had the impression the Agency officials were not quite taking it all in: "They did not, as we did in Budapest, look daily at death."

Interim agreement (29 May)

In the meantime, the Agency gave Brand a piece of paper dated 29 May, referred to as an "interim agreement" (which Brand called a Protokoll in three books he later wrote about the proposal), purporting to be a written agreement that it would accept Eichmann's offer in principle. The document promised the Germans $4,000 for each 1,000 Jewish emigrants to Palestine, and one million Swiss francs for each 1,000 Jewish emigrants to Spain. In return for allowing the Allies to supply goods to the Jews in the concentration camps, the Germans would receive equivalent supplies for themselves.

Rose writes that the interim agreement was really intended only to allow Brand to return to Budapest; had he returned empty-handed, he risked having himself and his family killed by the SS. He sent his wife a telegram on 27 May to tell her about the agreement, hoping she would tell Eichmann and that this might delay the deportations, and after receiving no response, sent another on 31 May, telling her that he intended to leave for Budapest on 4 June. Unknown to him, both his wife and Rudolf Kastner had been held in Budapest between 27 May and 1 June by the Hungarian Arrow Cross. They first received news of the agreement when they were released. Rose reports that Eichmann rejected it as inadequate, though Hansi Brand later testified that Eichmann saw it as a "good token."

The text of this document was sent by the Jewish Agency in Istanbul by diplomatic courier, arriving in Budapest on 7 July. Kastner took it straight to Eichmann and Kurt Becher. Kastner said he asked Becher whether the interim agreement was sufficient to open negotiations regarding all the Jews held by the Germans. Becher reportedly said that Himmler might agree. In the meantime, Kastner asked for two things. First, he requested that a trainload of over 1,600 Jews he had arranged to travel to Switzerland, thanks to a separate series of negotiations with Eichmann (see Kastner train), be allowed to resume its journey; the train had been diverted, for reasons that remain unclear, to the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen. And secondly, he asked that no further Jews from Budapest be deported. Becher agreed, but said he had to seek approval from Himmler.

Arrested by British intelligence (7 June)

In Istanbul it became clear to Brand that Moshe Sharett was not going to arrive. Brand was told Sharett had been refused a visa and that the British were actively preventing him from travelling to Turkey. Brand was asked instead to travel to Aleppo on the Syrian-Turkish border to meet Sharett. He was reluctant, because the area was under British control, and he was afraid the British would want to question him. However, he was persuaded to go, and left by train, accompanied by two members of the Jewish Agency.

On the train, Brand became even more nervous after being approached by men who said they were agents of Zeev Jabotinsky's Hatzohar party (Alliance of Zionists-Revisionists Party) and the World Agudath Israel Orthodox religious party. They told him that the British were going to arrest him in Aleppo. "Die Engländer sind in dieser Frage nicht unsere Verbündeten," they told him ("the British are not our allies in this matter"). If he continued with his journey, he would not be allowed to return to Hungary, they said.

Brand later told the court during Adolph Eichman's trial in Israel that he was terrified when he heard this, because not returning to Budapest within the time frame specified by Eichmann meant "the failure of my mission and the extermination of my family and a million other Jews in Hungary." He was assured by one of his travelling companions from the Jewish Agency that nothing was going to happen to him in Aleppo, and he wanted to believe this: "I could not believe that England – this land which alone fought on while all other countries of Europe surrendered to despotism – that this England which we had admired as the inflexible fighter for freedom wanted simply to sacrifice us, the poorest and weakest of all the oppressed."

After arriving in Ankara, the men continued by train to Aleppo. According to Ben Hecht, just before arriving, the Jewish Agency official who had assured Brand he would not be arrested told him that, should he indeed be picked up by the British, he was not to speak to them without a member of the Agency present. Hecht argues that this was the ultimate betrayal. Not only had the Agency effectively handed Brand over to the British, Hecht says, but they also acted to ensure he remain silent unless the Agency itself gave him permission to speak. As soon as Brand arrived in Aleppo on 7 June, he was arrested by two men in plain clothes who blocked his way, then pushed him into a Jeep waiting with its engine running. He discovered later they were British intelligence.

Reasons for the arrest

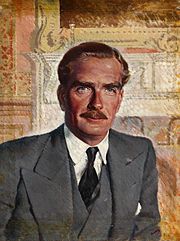

According to Raul Hilberg, details of Brand's business in Istanbul had been passed to London and Washington. The Cabinet Committee on Refugees in London, which included British Foreign Secretary (later Prime Minister) Anthony Eden and Colonial Secretary Oliver Stanley, had considered the "blood for goods" proposal, and had decided against pursuing it. If the suggestion had indeed come from the SS, it was a clear case of blackmail, and in any event, supplying extra trucks would have strengthened the enemy's hand, writes Hilberg. In addition, he writes, to leave the selection of refugees to be saved up to the Nazis, without considering the interests of Allied prisoners, would leave the British government opened to domestic criticism.

Bauer stresses other factors in the British decision. The British were convinced they were dealing with a Himmler trick of some kind, he writes, possibly an attempt to strike up a separate peace deal with the West in order to cause a rift between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. Bauer also writes that, if the deal had gone through, and large numbers of Jews had been released from Nazi-held territories, a consequence of them being transported through central Europe would have been to halt Allied airborne military operations, and possibly also land-based ones, turning the Jews, in effect, into human shields. Bauer believes the British feared this may have been Himmler's primary motive in proposing the deal, because the suspension of Allied attacks would have allowed the Germans to concentrate more of their forces against the East.

Brand's failure to return to Budapest within the two weeks expected by Eichmann was regarded as a disaster by other members of the Aid and Rescue Committee. A report written by Kastner states that Eichmann started demanding that Brand return, and wanted a "clear-cut answer" as to whether the proposal had been accepted. The report says: "We had to explain to him every day that discussions on this matter between London, Washington, and Moscow could be protracted. There were enough reasons for delay. Apparently the Allies could not easily be brought to a common denominator about such a delicate matter. The continuation of the deportations of Hungarian Jews was complicating the negotiations." On page 48 of the report, Kastner wrote "on June 9 Eichmann said, 'If I do not receive a positive reply within three days, I shall operate the mill at Auschwitz'." ("Ich lasse die Muehle laufen.")

Brand testified that he was taken to an elegant Arab villa where some high-ranking British officers were staying, and on June 11 was introduced to Moshe Sharett with whom he spoke during two sessions of six hours each. Sharett wrote in his report of 27 June 1944: "I must have looked a little incredulous, for he said: 'Please believe me: they have killed six million Jews; there are only two million left alive'." After the second session, Sharett spoke to British officials and turned again to Brand, telling him: "Dear Joel, I have to tell you something bitter now." He told Brand he would have to go south, not back to Budapest, because the British had demanded it. Brand reportedly started screaming:

Do you know what you are doing? This is simply murder! That is mass murder. If I don't return our best people will be slaughtered! My wife! My mother! My children will be first! ... I have come here under a flag of truce. I have brought you a message. You can accept or reject, but you have no right to hold the messenger ...

Despite his protests, Brand was taken to Cairo, where he was questioned by the British for days. On the 10th day, he went on hunger strike, writing in a letter to the Jewish Agency: "It is apparent to me now that an enemy of our people is holding me and does not intend to release me in the near future. I have decided to go on a hunger strike again and will do my utmost to break through the bayonets guarding me." On the 17th day, he was handed a note from one of the Jewish Agency men with whom he had travelled to Aleppo, urging him not to be difficult.

Brand later testified that Lord Moyne, the British Minister Resident in the Middle East, and a close friend of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, was present during one of the interrogations and is alleged to have said: "What can I do with this million Jews? Where can I put them?" Moyne was assassinated in Cairo a few months later, on 6 November 1944, by Eliyahu Bet-Zuri and Eliyahu Hakim of the Lehi (Stern Gang). Ben Hecht writes that Ehud Avriel, the Jewish Agency official who had accompanied Brand to Aleppo and told him the British would not arrest him, insisted it was not Lord Moyne who had said this, and asked Brand not to repeat Moyne's name in Brand's autobiography, Advocate for the Dead, but Brand repeated the allegation under oath during Eichmann's trial. During a meeting with Moshe Sharett on 6 July 1944, Anthony Eden expressed his sympathy regarding the decision to block the negotiations with Eichmann, but said he had to act in unison with the United States and Soviet Union.

British release Brand (October)

The British released Brand in October 1944 but, according to Ben Hecht, would not allow him to return to Hungary, compelling him instead to travel to Palestine. Bauer disputes this, arguing that the story of Brand being forced to go to Palestine was spread around Israel during the 1953 libel trial in Jerusalem of Malchiel Greenwald, a freelance writer who, in a self-published pamphlet, had accused Brand's colleague on the Aid and Rescue Committee, Rudolf Kastner (by then an Israeli government spokesman), of having collaborated with the Nazis. The Israeli government sued Greenwald on Kastner's behalf, and Brand offered testimony about his and Kastner's contacts with Eichmann, and the "blood for goods" proposal. The Israeli government lost the case, the judge alleging that Kastner had indeed "sold his soul to the devil" in his dealings with Eichmann, and although the decision was overturned on appeal, Kastner had already been assassinated.

In fact, writes Bauer, by the time the British released Brand, he was afraid to return to Budapest, convinced the Germans would murder him, so he chose instead to travel to Palestine. Once there, he tried to contact Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization. Weizmann responded by saying that his secretary would arrange an appointment for them to meet, an appointment that Brand said was never made.

Himmler's involvement in the proposal

Bauer writes that we know the deal originated with Himmler because a cable from Edmund Veesenmayer of the SS to the German Foreign Office on 22 July 1944 stated that Brand and Grosz had been sent to Turkey on the orders of Himmler. SS officer Kurt Becher also indicated that his orders came directly from Himmler: "So I came into contact with Joel Brand ... Trucks were a big problem. So trucks were discussed, 10,000 trucks that is. There were many discussions. Himmler said to me: 'Take whatever you can from the Jews. Promise them whatever you want. What we will keep is another matter'."

Eichmann himself later testified that the order came from Himmler, and a report from Kastner shows that Eichmann did not seem happy about having to deal with Brand. Kastner wrote that when Brand failed to return from Istanbul, Eichmann said: "Yes. I saw all of this in advance. I warned Becher countless times not to allow himself to be led by the nose. If I do not receive a positive answer within forty eight hours, I will have all this Jewish bag of filth from Budapest laid low." ("Werde ich das ganze juedische Dreckpack von Budapest umlegen lassen.")

Bauer writes that the "clumsiness of the approach has been a wonderment to all observers." He argues that it is obvious that Eichmann was Himmler's reluctant messenger, and that Eichmann's own inclination was to continue murdering Jews, not to sell them. On the day Brand left for Vienna and Istanbul, Eichmann travelled to Auschwitz to make sure Rudolf Hoess, the commander of the camp, would be ready to receive the first arrivals scheduled to leave Hungary on 14 May. Hoess told him there would be problems processing such large numbers, whereupon Eichmann ordered that there should be no selections but that all the new arrivals should be gassed immediately, which does not indicate that he was willing to delay the exterminations until Brand returned from Istanbul, as Brand seemed to believe.

Bauer argues that the presence of Clages at the meetings signals that Himmler had changed the emphasis from "blood for goods" to secret talks aimed at peace. Bauer writes that there is no indication of what exactly Himmler wanted to achieve, because he did not commit his thoughts to paper, but Bauer points out that Brand and Grosz arrived in Istanbul just two months before the assassination attempt, on 20 July 1944, on Adolf Hitler, and that Himmler knew there was a plot, though did not know where and when it would be carried out. It is possible, Bauer argues, that Himmler wanted to open negotiations for peace in the event that Hitler did not survive, using two low-level agents, a Jew and a spy, in case he had to distance himself from their mission; and if Hitler did survive, Himmler could offer him the chance to conclude a separate peace deal with the West, excluding the Soviet Union.

Brand himself eventually adopted such a theory. Two months before his death, he spoke of his belief at the trial in Germany of Eichmann's deputies Hermann Krumey and Otto Hunsche that the "blood for goods" proposal had originated with Himmler, in an effort to drive a wedge between the Allies. "I made a terrible mistake in passing this on to the British. ... It is now clear to me that Himmler sought to sow suspicion among the Allies as a preparation for his much desired Nazi-Western coalition against Moscow."

Aftermath

In Budapest, the Vaada waited anxiously for Brand's return. On 27 May, Hansi Brand was arrested and beaten by the Hungarian Arrow Cross, though she testified at Eichmann's trial that she withstood it and gave them no information. Hilberg writes that the Vaada did not expect the Allies would actually supply goods to Eichmann, but it hoped for a gesture that would allow protracted negotiations with the Nazis to begin while the Jews waited for the arrival of the Red Army.

Brand's failure to return to Budapest meant the Vaada was thrown back on its own resources, bitter about the lack of help from the outside world, and in particular from Jews living in safe countries. Bauer argues that their mistake was to adopt the almost anti-Semitic belief in unlimited Jewish power. The committee believed that Jewish leaders could move freely during the war and could persuade the Allies to do whatever needed to be done to save the Jews of Hungary. They had similar trust in the goodwill and power of the Allies, but the latter were gearing up for the invasion of Normandy just as Brand set out on his mission, and "[a]t that crucial moment", writes Bauer, "to antagonize the Soviets because of some hare-brained Gestapo plan to ransom Jews was totally out of the question."

Rudolf Kastner wrote that the Vaada had no choice but to believe in the possibility of rescue. Of Jewish communities living in countries unaffected by the Holocaust, he wrote: "They were outside, we were inside. They moralized, we feared death. They had sympathy for us and believed themselves to be powerless; we wanted to live and believed rescue had to be possible."

Brand was a bitter man when he was finally released by the British. He joined the Lehi (Stern Gang), who were fighting to remove the British from Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The situation created a rift between him and his wife, who for many years wondered what the truth was behind her husband's failure to return in time. Bauer concludes that, despite the failure of the mission, Brand was an extremely courageous man who had passionately wanted to help the Jewish people, yet whose life was thereafter plagued by the suspicions of family and friends. Brand offered testimony in Israel and Germany about the "blood for goods" proposal during several trials, including that of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961, which saw Eichmann executed, and of Eichmann's assistant, Hermann Krumey, in Frankfurt in 1964. Ronald Florence writes that he seemed to live only to set the historical record straight. He died in 1964 of liver disease brought on by alcoholism, reportedly a broken man.