Grand Central Station (Chicago)

Background Information

SOS Children made this Wikipedia selection alongside other schools resources. Before you decide about sponsoring a child, why not learn about different sponsorship charities first?

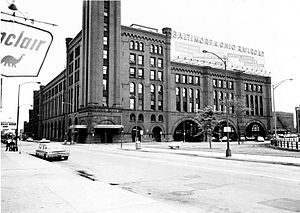

Grand Central Station was a passenger railroad terminal in downtown Chicago, Illinois, from 1890 to 1969. It was located at 201 W. Harrison Street in the south-western part of the Chicago Loop, the block bounded by Harrison Street, Wells Street, Polk Street and the Chicago River. Grand Central Station was designed by architect Solon Spencer Beman for the Wisconsin Central Railroad, and was completed by the Chicago and Northern Pacific Railroad.

Grand Central Station was eventually purchased by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which used the station as the Chicago terminus for its passenger rail service, including its glamorous Capitol Limited to Washington, D.C. Major tenant railroads included the Soo Line Railroad, successor to the Wisconsin Central, the Chicago Great Western Railway, and the Pere Marquette Railway. The station opened December 8, 1890, closed on November 8, 1969, and torn down in 1971.

Construction

In October 1889, a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Central Railroad (WC) began constructing a new passenger terminal at the southwest corner of Harrison Street and Wells Street (then called Fifth Avenue) in Chicago, to replace a temporary facility built nearby. The location of this new depot, along the south branch of the Chicago River, was selected to take advantage of the bustling passenger and freight market traveling on nearby Lake Michigan.

The station was executed in the Norman Castellated architectural style by architect Solon S. Beman, who had gained notoriety as the designer of the Pullman company neighbourhood. Constructed of brick, brownstone and granite, it was 228 feet (70 meters) wide on the side facing Harrison Street and 482 feet (147 meters) long on the side facing Wells. Imposing arches, crenellations, a spacious arched carriage-court facing Harrison Street, and a multitude of towers dominated the walls. Its most famous feature, however, was an impressive 247-foot (75 meter) tower at the northeast corner of the property. Beman, an early advocate of the Floating raft system to solve Chicago's unique swampy soil problems, designed the tower to sit within a floating foundation supported by 55-foot (16.8 meter) deep piles. Early on, an 11,000-pound (4,990 kilogram) bell in the tower rang in the hours. At some point, however, the bell was removed, but the tower (and its huge clock, 13 feet (4 meters) in diameter—at one time among the largest in the United States) remained.

The interior of the Grand Central Station was decorated as extravagantly as the exterior. The waiting room, for example, had marble floors, Corinthian-style columns, stained-glass windows and a marble fireplace, and a restaurant. The station also had a 100-room hotel, but accommodations ended late in 1901.

Not as famous as the clocktower but equally architecturally unique was Grand Central Station's self-supporting glass and steel train shed, 555 feet (169 meters) long, 156 feet (48 meters) wide and 78 feet (24 meters) tall, among the largest in the world at the time it was constructed. The trainshed, considered an architectural gem and a marvel of engineering long after it was built, housed six tracks and had platforms long enough to accommodate fifteen-car passenger trains. When it was finally completed, the station had cost its railroad owners one million dollars to build.

Grand Central Station was formally opened on December 8, 1890, by the Chicago and Northern Pacific Railroad, a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railway. Seeking access to the Chicago railway market, the Northern Pacific had purchased Grand Central and the trackage leading up to it from the Wisconsin Central with the intention of making the station its eastern terminus. When it opened, Grand Central hosted trains from the WC (which connected with its former trackage in Forest Park, Illinois), and the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad (M&NW), which made also a connection at Forest Park. By December 1891, the tenants also included the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and in 1903, the Pere Marquette Railway also started using the station.

Weakened by the prolonged economic downturn of the Panic of 1893, the Northern Pacific went bankrupt in October 1893, and was forced to end its ownership of the Chicago and Northern Pacific, including Grand Central Station. Ultimately, tenant railroad Baltimore and Ohio purchased the station at foreclosure in 1910 along with all the terminal trackage to form the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad (B&OCT).

Services

The smallest of Chicago's passenger rail terminals, Grand Central Station was a relatively quiet place, even during its heyday. Grand Central never became a prominent destination for large numbers of cross-country travelers, nor for the daily waves of commuters from the suburbs, that other Chicago terminals were. In 1912, for example, Grand Central served 3,175 passengers per day—representing only 4.5 percent of the total number for the city of Chicago—and serviced an average of 38 trains per day (including 4 B&O suburban trains). This number paled in comparison to the 146 trains served by Dearborn Station, the 191 by LaSalle Street Station, the 281 at Union Station, the 310 by the Chicago and North Western Terminal and the 373 trains per day at Central Station.

The station did host some of Baltimore and Ohio's most famous passenger trains, including the Capitol Limited to Washington, D.C.. Unfortunately, however, the circuitous trackage leading up to the station from the east led these trains miles out of their way through the industrial southwest and west side of the city (See map to the left). As for the other tenants, the Soo Line Railroad (which purchased the WC in 1909), the M&NW (which became known as the Chicago Great Western Railway in 1893), and the Pere Marquette Railway (which was merged into the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1947), none were anywhere near as serious players in the intercity passenger rail market as the B&O.

Intercity Passenger Trains

Grand Central Station served as a terminal for the following lines and intercity trains:

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad: Capitol Limited, Columbian, and Shenandoah to New York City and the Chicago - Washington Express to Washington, D.C., along with other trains to Cumberland, Maryland and Wheeling, West Virginia.

- Chicago Great Western Railway (until 1956): Legionnaire, later Minnesotan, both to Minneapolis, Minnesota. Other trains to Kansas City, Missouri and Omaha, Nebraska.

- Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie Railway (Soo Line) (until 1899, and from 1912 to 1965; used Central Station in between and after): Laker to Duluth, Minnesota.

- Pere Marquette Railway: Grand Rapids Flyer and Grand Rapids Express to Grand Rapids and Muskegon, Michigan and, ultimately to Buffalo, New York. Upon the 1947 merger with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, PM trains were renamed Pere Marquette.

- From December 1900 to July 1903, the New York Central Railroad and Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad used Grand Central, as their LaSalle Street Station was being rebuilt.

Suburban Commuter Trains

In addition to intercity passenger rail service, Grand Central Station hosted several short-lived intraurban passenger rail operations. To coincide with the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, the Baltimore and Ohio operated a special passenger train between Grand Central Station and Jackson Park, with intermediate stops at Halsted Street, Blue Island Avenue, Ashland Avenue and Ogden Avenue. Grand Central Station also served as a terminal for at least two suburban commuter lines. One, operated by the Wisconsin Central, ran trains west of Grand Central Station to Altenheim. The second was begun by the Chicago Terminal Transfer Railroad in 1900, and continued when the line was purchased by the B&O in 1910. It operated six trains a day between Grand Central and Chicago Heights, stopping in Blue Island, Harvey, Thornton and Glenwood. The line was unsuccessful and ended as early as 1915. None of the other tenant railroads operated commuter trains out of Grand Central Station.

The end

The lightly used terminal became even quieter in the years following World War II, with Grand Central serving 26 intercity passenger trains, down from nearly 40 at its busiest. Passenger trains were dropped and service was curtailed, and by 1956 the Chicago Great Western, which as late as 1940 had run six trains per day in and out of Grand Central stopped operating passenger service into Chicago altogether. As a result, by 1963 only ten intercity trains remained, of which six were operated by the Baltimore and Ohio. The number of passengers that used the remaining service shrank proportionately: by 1969, the year the station closed, the station only served an average of 210 passengers per day.

Due to its small size, its age and perceived obsolescence, Grand Central was the target of a long-term political effort by the city government to encourage consolidation of passenger terminals in the south Loop. It was ultimately this political effort that sealed the fate of Grand Central, described in 1969 as "decaying, dreary, and sadly out of date".

Faced with decreasing passenger numbers and intense political pressure to consolidate, the railroads operating into Grand Central Station re-routed their trains into other Chicago terminals, beginning with the Soo Line into Central Station in 1963. The remaining six Baltimore and Ohio and ex-Pere Marquette trains last used Grand Central Station on November 8, 1969 and were routed into their new terminus at the Chicago and North Western Terminal the following day.

Sitting unused, Grand Central Station's value as an architectural and engineering masterpiece was discounted by its railroad owner, who believed the value of the land for urban redevelopment to be quite substantial. As a result, the trackage was scrapped and the entire terminal was razed by the railroad in 1971.

Present-day

Approximately 11 acres remain vacant between Harrison and Polk; the site currently serves as a de facto dog park in the South Loop. Just south of the site a single 17-story apartment building was constructed, the only construction of a planned development known as River City (designed by Bertrand Goldberg who also designed the landmark " Marina City" along the main branch of the Chicago River), was constructed on the former coach yard and approaches to the terminal. River City was meant to be a complex of three 68-story office and residential towers stretching along the Chicago River from Harrison to Roosevelt Road, but only the smaller apartment building was ever completed. Plans for an office tower, condominiums, or retail development on the Grand Central Station terminal site have all been proposed over the past several years, and all have been shelved.

The land on the corner of Harrison and Wells, the lot on which the station itself stood, remains vacant. In March 2008, CSX Transportation—the successor company to the B&O—sold the property to a Skokie, Illinois based capital group with the intent of redeveloping the site with mixed-use high-rise buildings.

Legacy

More than thirty years after its destruction, Grand Central Station has only relatively recently been identified by local historians, railroad enthusiasts and architecture critics as "the queen of the city's old train stations". Author Carl W. Condit remarked that the station was "an important Chicago building even if it never received much recognition". Architect Harry Weese bemoaned its "wanton destruction". Ira J. Bach noted that when the terminal was demolished: "Chicago lost its greatest monument to the institution which had created it: the railroad."

The B&OCT Bascule Bridge

At the time Grand Central was completed, passenger trains approached the terminal by crossing the Chicago River to the southwest over a bridge between Taylor Street and Roosevelt Road, constructed in 1885. This first bridge was replaced by a taller structure in 1901 to accommodate larger boats and ships on the south branch of the river. When the Chicago River was straightened and widened in the 1930s, the United States Department of War insisted the Baltimore and Ohio build a new bridge adjacent to that of the St. Charles Air Line Railroad which crossed the river between 15th and 16th Streets. The new bridge's location, about seven blocks south of its previous crossing, exacerbated the circuitous route of the B&OCT trackage leading to Grand Central Station. Both the B&O bridge, and that of the St. Charles Air Line immediately adjacent to it, were built in 1930, and both are bascule bridges.

The B&OCT bridge sits unused. However, it was not dismantled and currently sits locked in the "open" position. Because they are bascule bridges, both the B&OCT and the Air Line bridges each have a counterweight of their own, and in this case, they share a common third counterweight between them. This design allowed them to operate in unison, with an operator from the B&OCT in charge of operating both bridges. This has led to a curious historical oddity, as the CSX, successor railroad to the B&O, owns a bridge that it cannot abandon, because the bridge is needed to continue operating a second bridge it does not own. An uncertain future awaits the old B&OCT bridge: the trackage it once served may never be rebuilt; or the bridge may find new life if Chicago continues its railroad heritage and becomes the hub of a planned national high speed rail network, thus possibly making use of the railway bridge once again.