Equivalence relation

Did you know...

SOS Children volunteers helped choose articles and made other curriculum material Before you decide about sponsoring a child, why not learn about different sponsorship charities first?

In mathematics, an equivalence relation is a binary relation between two elements of a set which groups them together as being "equivalent" in some way. Let a, b, and c be arbitrary elements of some set X. Then "a ~ b" or "a ≡ b" denotes that a is equivalent to b.

An equivalence relation "~" is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. In other words, the following must hold for "~" to be an equivalence relation on X:

- Reflexivity: a ~ a

- Symmetry: if a ~ b then b ~ a

- Transitivity: if a ~ b and b ~ c then a ~ c.

The equivalence class a under "~", denoted [a], is the subset of X whose elements b are such that a~b. X together with "~" is called a setoid.

Examples of equivalence relations

A ubiquitous equivalence relation is the equality ("=") relation between elements of any set. Other examples include:

- "Has the same birthday as" on the set of all people, given naive set theory.

- "Is similar to" or "congruent to" on the set of all triangles.

- "Is congruent to modulo n" on the integers.

- "Has the same image under a function" on the elements of the domain of the function.

- Logical equivalence of logical sentences.

- "Is isomorphic to" on models of a set of sentences.

- In some axiomatic set theories other than the canonical ZFC (e.g., New Foundations and related theories):

- Similarity on the universe of well-orderings gives rise to equivalence classes that are the ordinal numbers.

- Equinumerosity on the universe of:

- Finite sets gives rise to equivalence classes which are the natural numbers.

- Infinite sets gives rise to equivalence classes which are the transfinite cardinal numbers.

- Let a, b, c, d be natural numbers, and let (a, b) and (c, d) be ordered pairs of such numbers. Then the equivalence classes under the relation (a, b) ~ (c, d) are the:

- Integers if a + d = b + c;

- Positive rational numbers if ad = bc.

- Let (rn) and (sn) be any two Cauchy sequences of rational numbers. The real numbers are the equivalence classes of the relation (rn) ~ (sn), if the sequence (rn − sn) has limit 0.

- Green's relations are five equivalence relations on the elements of a semigroup.

- "Is parallel to" on the set of subspaces of an affine space.

Examples of relations that are not equivalences

- The relation "≥" between real numbers is reflexive and transitive, but not symmetric. For example, 7 ≥ 5 does not imply that 5 ≥ 7. It is, however, a partial order.

- The relation "has a common factor greater than 1 with" between natural numbers greater than 1, is reflexive and symmetric, but not transitive. (The natural numbers 2 and 6 have a common factor greater than 1, and 6 and 3 have a common factor greater than 1, but 2 and 3 do not have a common factor greater than 1).

- The empty relation R on a non-empty set X (i.e. aRb is never true) is vacuously symmetric and transitive, but not reflexive. (If X is also empty then R is reflexive.)

- The relation "is approximately equal to" between real numbers or other things, even if more precisely defined, is not an equivalence relation, because although reflexive and symmetric, it is not transitive, since multiple small changes can accumulate to become a big change.

- The relation "is a sibling of" on the set of all human beings is not an equivalence relation. Although siblinghood is symmetric (if A is a sibling of B, then B is a sibling of A) it is neither reflexive (no one is a sibling of himself), nor transitive (since if A is a sibling of B, then B is a sibling of A, but A is not a sibling of A). Instead of being transitive, siblinghood is "almost transitive", meaning that if A ~ B, and B ~ C, and A ≠ C, then A ~ C.

- The concept of parallelism in ordered geometry is not symmetric and is, therefore, not an equivalence relation.

- An equivalence relation on a set is never an equivalence relation on a proper superset of that set. For example R = {(1,1), (1,2), (1,3), (2,1), (2,2), (2,3), (3,1), (3,2), (3,3)} is an equivalence relation on {1,2,3} but not on {1,2,3,4} or on the natural number. The problem is that reflexivity fails because (4,4) is not a member.

Connection to other relations

A congruence relation is an equivalence relation whose domain X is also the underlying set for an algebraic structure, and which respects the additional structure. In general, congruence relations play the role of kernels of homomorphisms, and the quotient of a structure by a congruence relation can be formed. In many important cases congruence relations have an alternative representation as substructures of the structure on which they are defined. E.g. the congruence relations on groups correspond to the normal subgroups.

Order and equivalence relations are both transitive, but only equivalence relations are symmetric as well. If symmetry is weakened to antisymmetry, the result is a partial order.

A partial equivalence relation is transitive and symmetric, but not reflexive.

- Transitive and symmetric imply reflexive iff for all a,b∈X, a~b is always defined.

A dependency relation is reflexive and symmetric, but not transitive.

A preorder is reflexive and transitive, but neither symmetric nor antisymmetric.

A strict partial order is transitive alone.

Equivalence relations can thus be seen as the culmination of a hierarchy of order relations.

Equivalence class, quotient set, partition

Let X be a nonempty set with typical elements a and b. Some definitions:

- The set of all a and b for which a ~ b holds make up an equivalence class of X by ~. Let [a] =: {x ∈ X : x ~ a} denote the equivalence class to which a belongs. Then all elements of X equivalent to each other are also elements of the same equivalence class: ∀a, b ∈ X (a ~ b ↔ [a ] = [b ]).

- The set of all possible equivalence classes of X by ~, denoted X/~ =: {[x] : x ∈ X}, is the quotient set of X by ~. If X is a topological space, there is a natural way of transforming X/~ into a topological space; see quotient space for the details.

- The projection of ~ is the function π : X → X/~, defined by π(x) = [x ], mapping elements of X into their respective equivalence classes by ~.

- Theorem on projections (Birkhoff and Mac Lane 1999: 35, Th. 19): Let the function f: X → B be such that a ~ b → f(a) = f(b). Then there is a unique function g : X/~ → B, such that f = gπ. If f is a surjection and a ~ b ↔ f(a) = f(b), then g is a bijection.

- The equivalence kernel of a function f is the equivalence relation, denoted Ef, such that xEfy ↔ f(x) = f(y). The equivalence kernel of an injection is the identity relation.

- A partition of X is a set P of subsets of X, such that every element of X is an element of a single element of P. Each element of P is a cell of the partition. Moreover, the elements of P are pairwise disjoint and their union is X.

Theorem ("Fundamental Theorem of Equivalence Relations": Wallace 1998: 31, Th. 8; Dummit and Foote 2004: 3, Prop. 2):

- An equivalence relation ~ partitions X.

- Conversely, corresponding to any partition of X, there exists an equivalence relation ~ on X.

In both cases, the cells of the partition of X are the equivalence classes of X by ~. Since each element of X belongs to a unique cell of any partition of X, and since each cell of the partition is identical to an equivalence class of X by ~, each element of X belongs to a unique equivalence class of X by ~. Thus there is a natural bijection from the set of all possible equivalence relations on X and the set of all partitions of X.

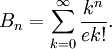

Counting possible partitions. Let X be a finite set with n elements. Since every equivalence relation over X corresponds to a partition of X, and vice versa, the number of possible equivalence relations on X equals the number of distinct partitions of X, which is the nth Bell number Bn:

Generating equivalence relations

- Given any set X, there is an equivalence relation over the set of all possible functions X→X. Two such functions are deemed equivalent when their respective sets of fixpoints have the same cardinality, corresponding to cycles of length one in a permutation. Functions equivalent in this manner form an equivalence class on X2, and these equivalence classes partition X2.

- An equivalence relation ~ on X is the equivalence kernel of its surjective projection π : X → X/~. (Birkhoff and Mac Lane 1999: 33 Th. 18). Conversely, any surjection between sets determines a partition on its domain, the set of preimages of singletons in the codomain. Thus an equivalence relation over X, a partition of X, and a projection whose domain is X, are three equivalent ways of specifying the same thing.

- The intersection of any two equivalence relations over X (viewed as a subset of X × X) is also an equivalence relation. This yields a convenient way of generating an equivalence relation: given any binary relation R on X, the equivalence relation generated by R is the smallest equivalence relation containing R. Concretely, R generates the equivalence relation a ~ b iff there exist elements x1, x2, ..., xn in X such that a = x1, b = xn, and (xi,xi+ 1)∈R or (xi+1,xi)∈R, i = 1, ..., n-1.

- Note that the equivalence relation generated in this manner can be trivial. For instance, the equivalence relation ~ generated by:

- The binary relation ≤ has exactly one equivalence class, X itself, because x ~ y for all x and y;

- An antisymmetric relation has equivalence classes that are the singletons of X.

- Let r be any sort of relation on X. Then r ∪ r−1 is a symmetric relation. The transitive closure s of r ∪ r−1 assures that s is transitive and reflexive. Moreover, s is the "smallest" equivalence relation containing r, and r/s partially orders X/s.

- Equivalence relations can construct new spaces by "gluing things together." Let X be the unit Cartesian square [0,1] × [0,1], and let ~ be the equivalence relation on X defined by ∀a, b ∈ [0,1] ((a, 0) ~ (a, 1) ∧ (0, b) ~ (1, b)). Then the quotient space X/~ can be naturally identified with a torus: take a square piece of paper, bend and glue together the upper and lower edge to form a cylinder, then bend the resulting cylinder so as to glue together its two open ends, resulting in a torus.

Algebraic structure

Modular lattices

The possible equivalence relations on any set X, when ordered by set inclusion, form a modular lattice, called Con X by convention. The canonical map ker: X∧X → Con X, relates the monoid X^X of all functions on X and Con X. ker is surjective but not injective. Less formally, the equivalence relation ker on X, takes each function f: X→X to its kernel ker f. Likewise, ker(ker) is an equivalence relation on X^X.

Group theory

It is very well known that lattice theory captures the mathematical structure of order relations. It is less known that transformation groups (some authors prefer permutation groups) and their orbits shed light on the mathematical structure of equivalence relations. Just as order relations are grounded in ordered sets, sets closed under pairwise supremum and infimum, equivalence relations are grounded in partitioned sets, sets closed under bijections preserving partition structure. Since all such bijections map an equivalence class onto itself, such bijections are also known as permutations.

Let '~' denote an equivalence relation over some nonempty set A, called the universe or underlying set. Let G denote the set of bijective functions over A that preserve the partition structure of A: ∀x ∈ A ∀g ∈ G (g(x) ∈ [x]). Then the following three connected theorems hold (Van Fraassen 1989: §10.3):

- ~ partitions A into equivalence classes. (This is the Fundamental Theorem of Equivalence Relations, mentioned above);

- Given a partition of A, G is a transformation group under composition, whose orbits are the cells of the partition‡;

- Given a transformation group G over A, there exists an equivalence relation ~ over A, whose equivalence classes are the orbits of G. (Wallace 1998: 202, Th. 6; Dummit and Foote 2004: 114, Prop. 2).

In sum, given an equivalence relation ~ over A, there exists a transformation group G over A whose orbits are the equivalence classes of A under ~.

This transformation group characterisation of equivalence relations differs fundamentally from the way lattices characterize order relations. The arguments of the lattice theory operations meet and join are elements of some universe A. Meanwhile, the arguments of the transformation group operations composition and inverse are elements of a set of bijections, A → A.

Moving to groups in general, let H be a subgroup of some group G. Let ~ be an equivalence relation on G, such that a ~ b ↔ (ab−1 ∈ H). The equivalence classes of ~—also called the orbits of the action of H on G—are the right cosets of H in G. Interchanging a and b yields the left cosets.

For more on group theory and equivalence relations, see Lucas (1973: §31).

‡Proof (adapted from Van Fraassen 1989: 246). Let function composition interpret group multiplication, and function inverse interpret group inverse. Then G is a group under composition, meaning that ∀x ∈ A ∀g ∈ G ([g(x)] = [x]), because G satisfies the following four conditions:

- G is closed under composition. The composition of any two elements of G exists, because the domain and codomain of any element of G is A. Moreover, the composition of bijections is bijective (Wallace 1998: 22, Th. 6);

- Existence of identity element. The identity function, I(x)=x, is an obvious element of G;

- Existence of inverse function. Every bijective function g has an inverse g−1, such that gg−1 = I;

- Composition associates. f(gh) = (fg)h. This holds for all functions over all domains (Wallace 1998: 24, Th. 7).

Let f and g be any two elements of G. By virtue of the definition of G, [g(f(x))] = [f(x)] and [f(x)] = [x], so that [g(f(x))] = [x]. Hence G is also a transformation group (and an automorphism group) because function composition preserves the partitioning of A.

Category theory

The composition of morphisms central to category theory, denoted here by concatenation, generalizes the composition of functions central to transformation groups. The axioms of category theory assert that the composition of morphisms associates, and that the left and right identity morphisms exist. If all morphisms in a category were to have "inverses," the category would resemble a transformation group, whose close relation to equivalence relations has just been explained. A morphism f can be said to have an inverse when f is an automorphism, i.e., the domain and codomain of f are identical, and there exists a morphism g such that fg = gf = identity morphism. Hence the category-theoretic concept nearest to an equivalence relation is a category whose morphisms are all automorphisms.

Equivalence relations and mathematical logic

Equivalence relations are a ready source of examples or counterexamples. For example, an equivalence relation with exactly two infinite equivalence classes is an easy example of a theory which is ω- categorical, but not categorical for any larger cardinal number.

An implication of model theory is that the properties defining a relation can be proved independent of each other (and hence necessary parts of the definition) if and only if, for each property, examples can be found of relations not satisfying the given property while satisfying all the other properties. Hence the three defining properties of equivalence relations can be proved mutually independent by the following three examples:

- Reflexive and transitive: The relation ≤ on N. Or any preorder;

- Symmetric and transitive: The relation R on N, defined as aRb ↔ ab ≠ 0. Or any partial equivalence relation;

- Reflexive and symmetric: The relation R on Z, defined as aRb ↔ "a − b is divisible by at least one of 2 or 3." Or any dependency relation.

Properties definable in first-order logic that an equivalence relation may or may not possess include:

- The number of equivalence classes is finite or infinite;

- The number of equivalence classes equals the (finite) natural number n;

- All equivalence classes have infinite cardinality;

- The number of elements in each equivalence class is the natural number n.

Euclid anticipated equivalence

Euclid's The Elements includes the following "Common Notion 1":

- Things which equal the same thing also equal one another.

Nowadays, the property described by Common Notion 1 is called Euclidean (replacing "equal" by "are in relation with"). The following theorem connects Euclidean relations and equivalence relations:

Theorem. If a relation is Euclidean and reflexive, it is also symmetric and transitive.

Proof:

- (aRc ∧ bRc) → aRb [a/c] = (aRa ∧ bRa) → aRb [reflexive; erase T∧] = bRa → aRb. Hence R is symmetric.

- (aRc ∧ bRc) → aRb [symmetry] = (aRc ∧ cRb) → aRb. Hence R is transitive.

Hence an equivalence relation is a relation that is Euclidean and reflexive. The Elements mentions neither symmetry nor reflexivity, and Euclid probably would have deemed the reflexivity of equality too obvious to warrant explicit mention. If this (and taking "equality" as an all-purpose abstract relation) is granted, a charitable reading of Common Notion 1 would credit Euclid with being the first to conceive of equivalence relations and their importance in deductive systems.