Local climate adaptation in Ethiopia and Mali

Farmers and herders in African drylands are often considered as being on the front line of climate

change. Collaborative research between Action Against Hunger (ACF), Tearfund, and the Institute of

Development Studies (IDS), in Ethiopia and Mali showed a considerable capacity of households to

adapt to what they perceive as changing rainfall patterns, but also significant costs and barriers to

their responses.

Preliminary findings from the study, due to be published

in early 2010, illustrate some key areas for support to

strengthen adaptive capacity.

Changing risks and impacts

A perception of changing rainfall patterns features

prominently in both country case studies. Over the past

ten years, the rain has become increasingly unpredictable

and erratic; the seasonal rains have started later and

finished earlier. This is detrimental to people’s key assets,

cattle and farmland, which are vulnerable to climate

risks. Key trends that affect households’ ability to tackle

climate risks include increasingly limited livelihood

choices and reduced solidarity in times of stress.

Recurrent drought has significantly reduced harvests and

extended hunger gaps. Communities report an increasing

sense of fatigue in the face of the changes they are

experiencing. Even richer groups are experiencing

increasing losses of key assets from multiple shocks, and

an increasing feeling of insecurity.

Challenges to adaptation

A number of adaptive strategies were observed in

response to climate and other stressors, but many are

associated with costs to households’ livelihoods. For

example:

• Reduced pasture quality means herders adapt

by travelling farther and for longer periods with

their animals. However, yield from livestock is still

insufficient. Furthermore, conflict over grazing and

water resources has increased between local people

and those from different areas passing through.

• Poorer households often use labour migration in

times of need. However, this can reduce households’

abilities to look after their own farms, thus increasing

their vulnerability to future shocks.

• Formal and informal community and external

institutions have traditionally provided support during

drought. However, access to support from community

institutions is, to a large extent, dependent on gender

and wealth. Furthermore, as times have become

tougher for all, external institutions are only partially

able to fill the gaps in support that households need.

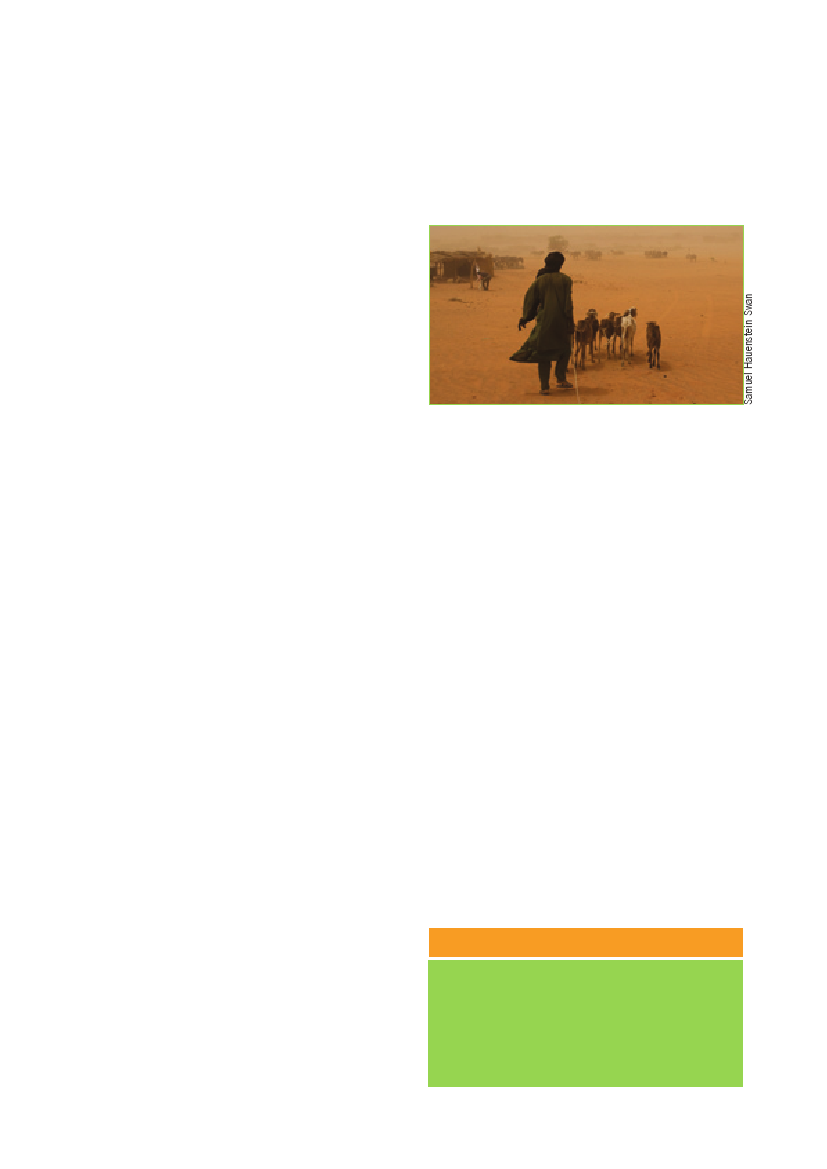

Livestock herder in Djebock, Mali

• Increase the options of the poorest people to diversify

their livelihoods, by improving their access to and

sustainable use of assets such as agricultural inputs,

natural resources and credit, particularly during

critical hunger periods.

• Strengthen existing local institutions with financial

and technical support so that they can boost

household strategies (regardless of the wealth, gender

or ethnic identity of household members) and fill gaps

in institutional support.

• Integrate adaptation into national development

policies, with a joined-up approach between

agriculture, water, nutrition, the environment, climate

change and disasters. Longer term programmes are

needed in order to effectively build resilience to

climatic and economic shocks.

Authors

Lars Otto Naess,

Institute of Development Studies,

University of Sussex, Brighton, UK.

Email: l.naess@ids.ac.uk.

Morwenna Sullivan,

Action Against Hunger.

Email: m.sullivan@aahuk.org.

Jo Khinmaung,

Tearfund.

Email: Jo.Khinmaung@tearfund.org

See also

Key recommendations

The following areas of action could strengthen existing

household adaptive capacity and community solidarity,

in order to avoid strategies that further increase

vulnerability.

Changing climates, changing lives: Adaptation

strategies among pastoral and agro-pastoral

communities in Ethiopia and Mali. By ACF

International, IDS, TEARFUND, IER, A-Z CONSULT,

ODES. In Press. http://tilz.tearfund.org/Research/

Food+and+Security+reports

3