Critical Thinking and Decision-Making

Why is it So Hard to Make Decisions?

The challenge of making decisions

No matter who you are or what you do for a living, you make thousands of minor decisions every day . Most are relatively inconsequential; for example, what do you want for breakfast? Do you want coffee, tea, or something else?

Other decisions are much more complex . Should you accept a new job? Should you move to a different city? What about buying a house, or starting a family? These decisions weigh more heavily because they can impact your life in many ways.

You might feel like you're bad at making decisions (or not good at making good ones). However, it's something we all struggle with due to the way our brains are made. Behind every decision, there are secret psychological factors that shape the way we think and act. Understanding these factors can make them easier to overcome.

Watch the video below to learn more about the psychology of decision-making.

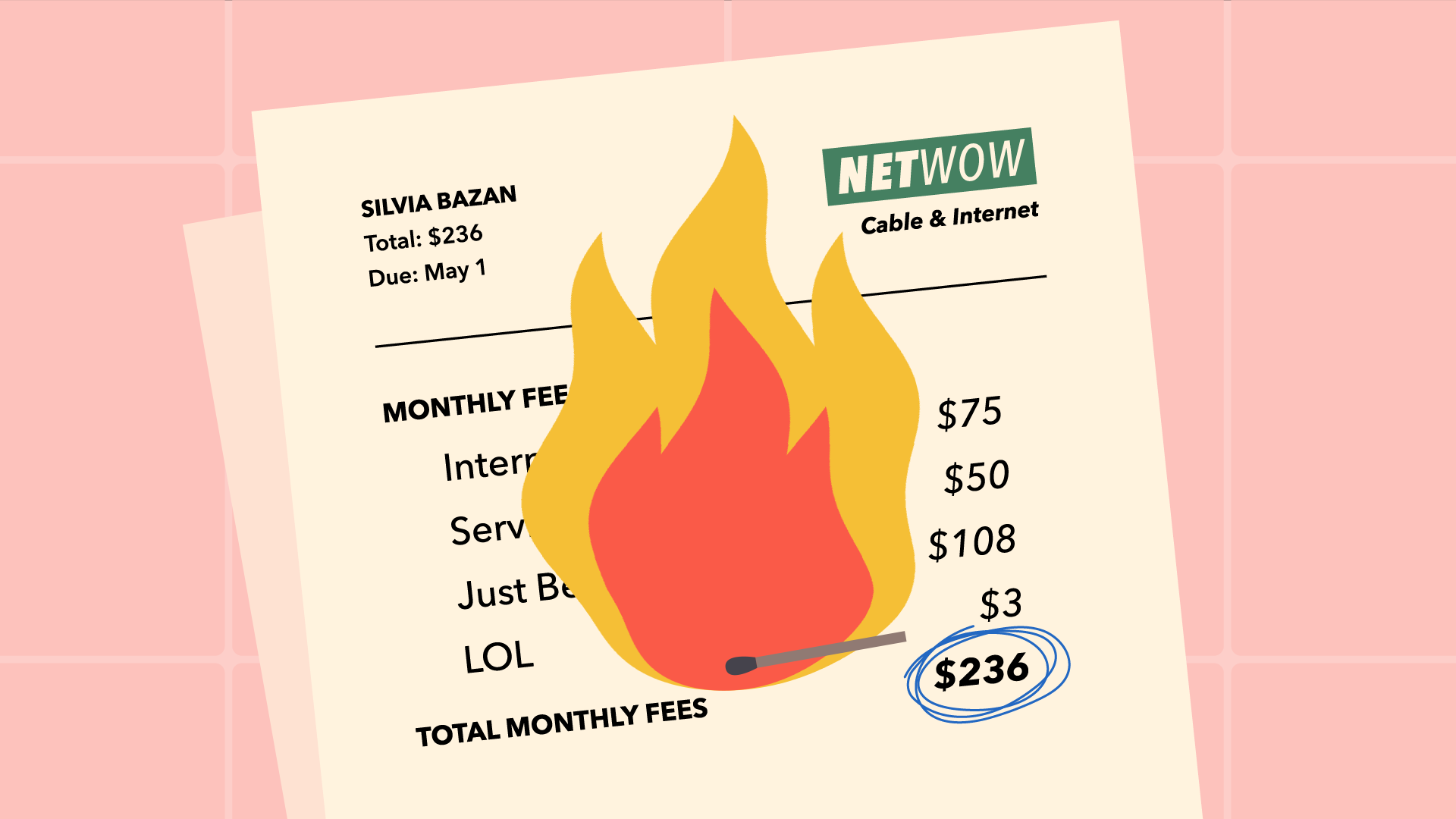

Status quo bias

Many missteps in decision-making can be chalked up to cognitive bias . That's our tendency to think a certain way without even realizing it. Here's a simple example: Have you ever avoided switching Internet providers, even though you were unhappy with your current service?

Something called status quo bias might be to blame. That's our tendency to stick with what we know, instead of choosing something new and different. We see the alternative as a risk or just not worth the trouble, even if it might be better. Without realizing it, we can become overly resistant to change.

Anchoring bias

Anchoring bias can also affect the choices we make. To understand how anchoring works, imagine you're shopping for a used car at a local dealership. The model you like is priced at $9,999.

Next, imagine the dealer offers you a discount. The car is now $8,999, a full thousand dollars less. Sounds like a can't-miss opportunity, right? Not necessarily.

Anchoring suggests that we rely too heavily on the first thing we hear (in this case, the initial price of the car). That's what makes the discount so appealing, but it shouldn't be the deciding factor. There are also more objective things to consider, like how much the car is really worth, and whether you can find a better price elsewhere. If you're not careful, the anchoring effect can weigh you down.

Choice overload

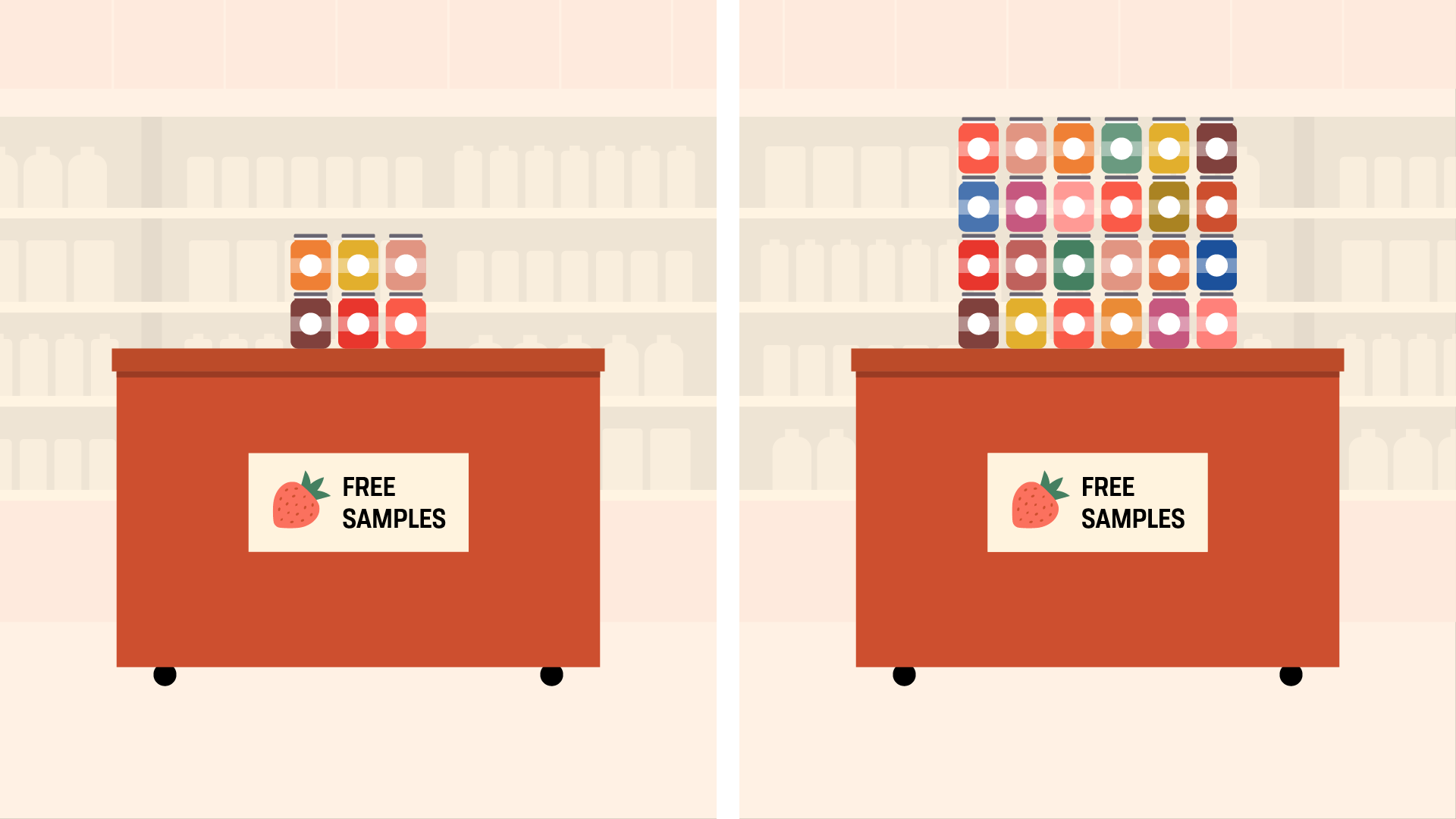

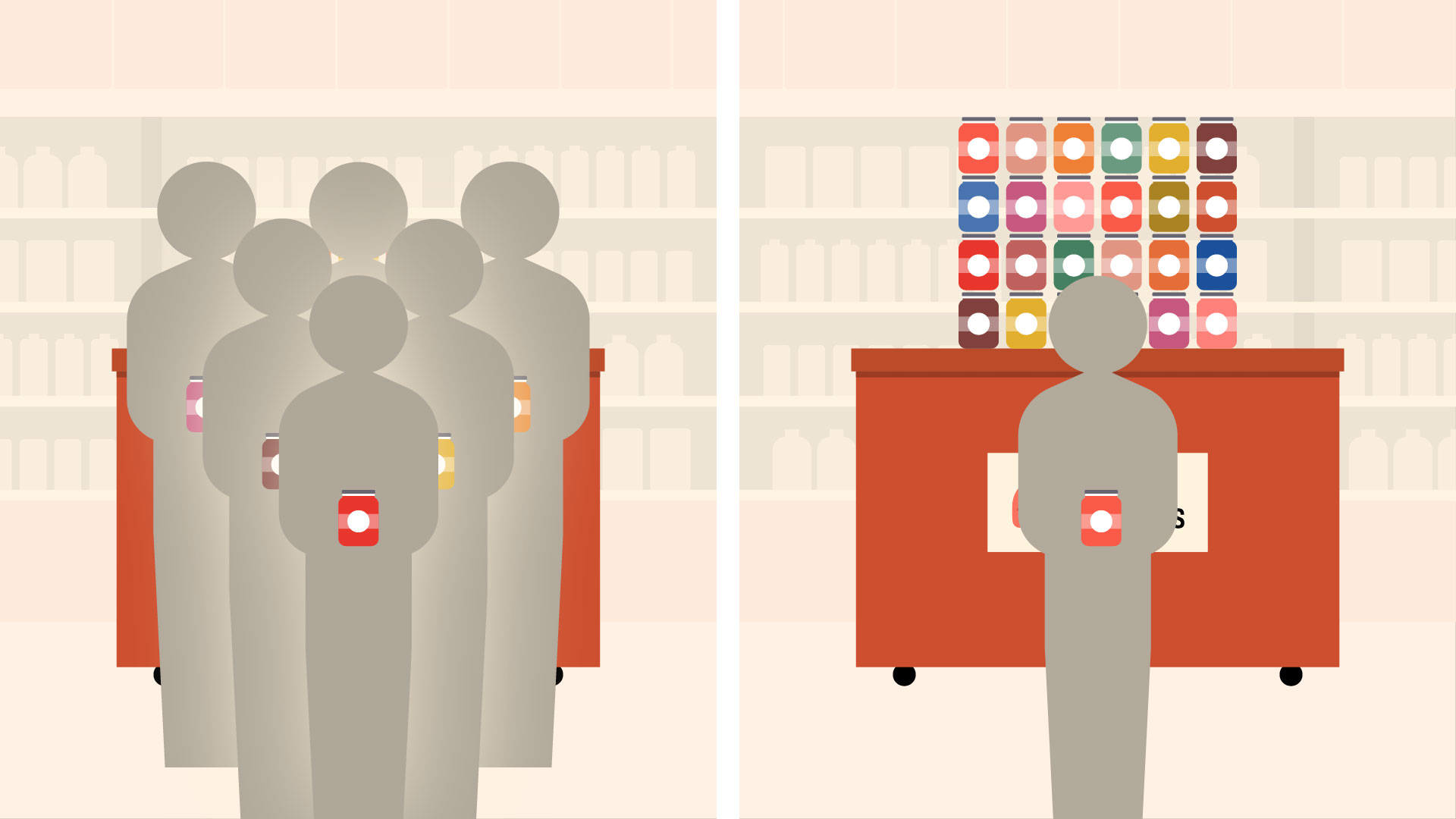

Cognitive biases aren't the only things that can affect decision-making. More and more studies show that stress can have an impact—both on the quality of our decisions and on our ability to make them. Take this well-known study about jam.

At an upscale food market, researchers set up two displays offering free samples of jam . One gave customers six different flavors to choose from; the other gave them 24.

The larger display attracted more people, but they were six times less likely to actually buy a jar of jam (compared to those who visited the smaller display). The reason for this is a phenomenon now known as choice overload .

Choice overload can happen any time we feel overwhelmed by the sheer number of options. We have such a hard time comparing them that we're less likely to choose anything at all. As in the jam example, many of us would sooner walk away empty-handed than deal with the stress of choosing from such a large selection.

Decision fatigue

A similar thing happens when we're forced to make multiple decisions one after another—a common occurrence in everyday life. We experience an effect psychologists call decision fatigue .

Decision fatigue suggests that making a large number of decisions over a prolonged period of time can be a significant drain on our willpower. The result? We have a harder time saying no —to things like junk food, impulse buys, and other tempting offers.

On the flip side, fatigue can also make it harder to say yes , especially to decisions that would upset the status quo.

Fatigue makes it difficult to even think about making decisions, let alone what's right or wrong, correct or incorrect. We follow the path of least resistance because it's the easiest thing to do.

The upside of uncertainty

Making decisions will always be difficult because it takes time and energy to weigh your options. Things like second-guessing yourself and feeling indecisive are just a part of the process.

In many ways, they're a good thing—a sign that you're thinking about your choices instead of just going with the flow. That's the first step to making better, more thoughtful decisions.